Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Showing posts with label fear. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fear. Show all posts

Saturday, April 25, 2020

The suchness of Earth Day.

This year Earth Day slipped by without my notice. Perhaps that was because I, like everyone else, was transfixed on COVID-19 and my top-of-mind priorities were thus in flux.

Seeing things as they truly are, without delusions or bias, is a serious challenge to world survival. The Buddha referred to himself as the Tathāgata, which is a derivative of the East Asian term Tathatā: the true basis of reality. Ordinarily, if we think of it at all, we think of spiritual awakening as some sort of magical state of mind. According to the 5th-century Chinese Mahayana scripture entitled Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana, the state of suchness/tathatā manifests in the highest wisdom with sublime attributes and is thus the womb of the Buddha.

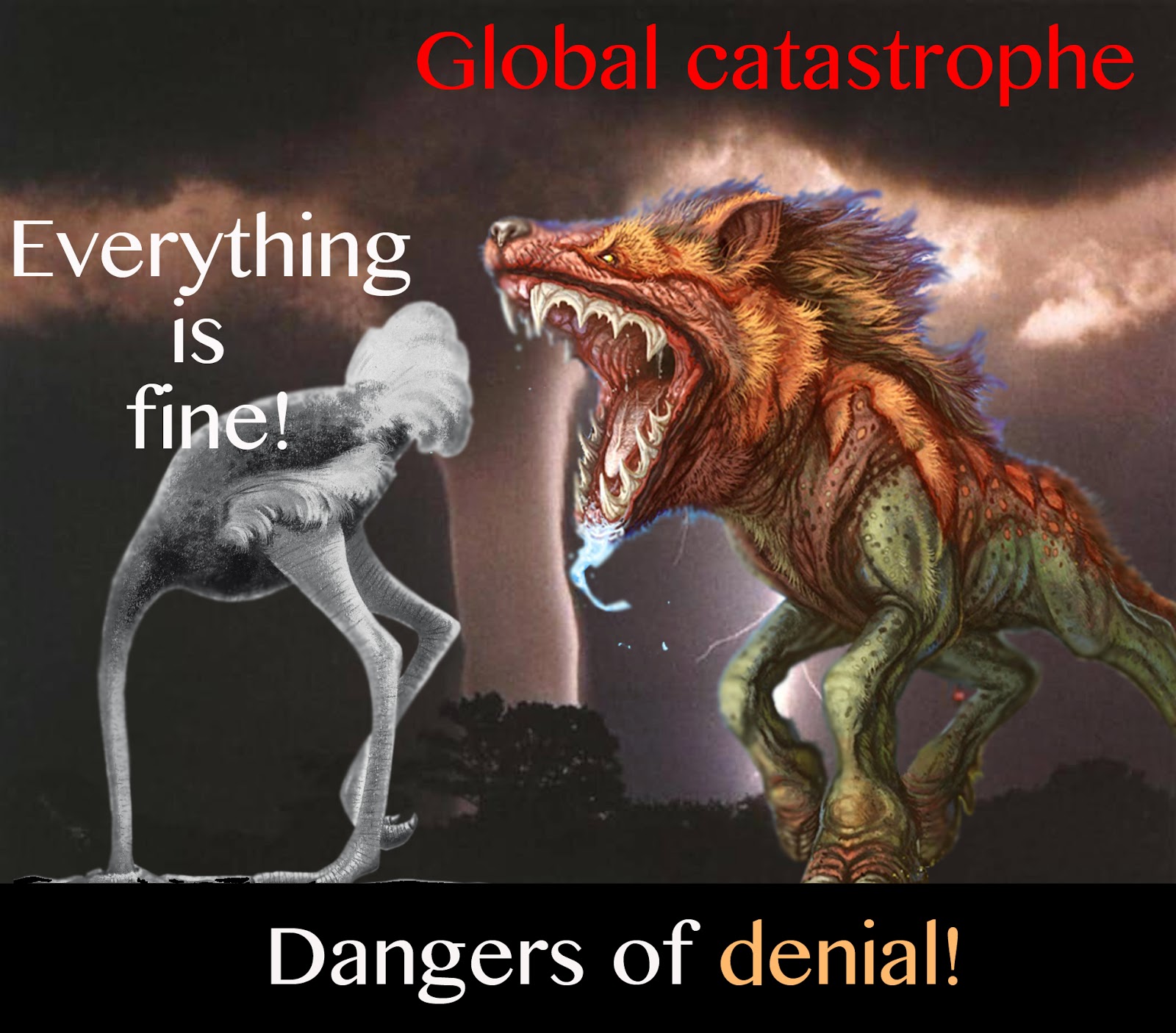

In the world of today, living in a state of denial represents a threat of massive proportions, not only to those who choose to stay blind but to us all. Putting one’s head in the sand of ignorance does not ensure safety. On the contrary, closing our eyes to the very real consequences of a warming climate accomplishes nothing more than ensuring the ultimate end of a world that enables life.

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

The four faces of us all.

|

| The distortions we imagine. |

There is a Japanese saying: “We have three faces: The first face, we show to the world. The second face, we show to our family and friends. The third face, we never show anyone and it is the truest reflection of who we are.”

There is, however, another Zen koan: “Who were you before your parents were born?” which transcends the first saying and points to our “original face”—Who all of us are before the clothing of expectations or definitions are applied is this original face, without form or definition—the one that can’t be seen that is doing the seeing. Look at it this way: If there is a face that can be perceived it can’t be who we are since it takes both a perceptible image (what is seen) and one who sees. All of us are that imperceptible seer, not an image.

The first face we show the world because we believe it is the expected ideal. The second face is the one we risk showing, based on the assumption that we can relax with family and friends: still a risk, but one we accept. The third face, the one we never show, is the one we fear the most and holds the greatest risk of exposure, persuading us that if ever revealed will destroy us. All three are unreal projections, based on our criteria within us that we construct. None of these are real. Instead, they are based on the expectations we each hold as yardsticks against which we measure who we imagine we are as acceptable beings, worthy of love.

The only face that is real is the fourth: the one that can’t be seen. This face alone holds no criteria of acceptability since by nature it is wholeness itself: complete, indiscriminate, lovable beyond measure and understanding of all, because IT is all.

Thursday, September 12, 2019

Earth we have a problem.

“Houston, we have a problem!” Those exact, iconic words, while capturing the essence of the situation, were not spoken by astronaut John Swigert during the Apollo 13 mission to the moon in 1970.

On the way, the lunar landing was aborted after an oxygen tank exploded, crippling the service module upon which the command module had depended. For some harrowing times following the explosion, it seemed nearly inevitable Apollo 13 would not only never reach the moon but would instead be lost in space forever. The message was timely. The engineering ground crew on earth found a solution, and the craft, along with those on board, were saved.

Fast forward 50 years to 2020 and that same iconic message applies, only it doesn’t concern an ordinary spacecraft. Instead, it concerns our spacecraft-earth, and we too have a problem. There is no ground crew of engineers, separate and apart from our craft since we are already on the ground, and there is nobody but us to fix our problem. And what’s the problem? We have created a use-it-and-lose-it, planned obsolescent, throw-away society and are paying the inevitable price.

Our military is an anomaly: Our warriors are expendable, are supposed to die a death of glory and valor, so as to justify and further promote wars for the sole purpose of filling the pockets of the war-mongers. And that requires greater and ever greater numbers of the treasures of our youth, along with the myth of nobility and honor, yet not become a liability to society, as costly veterans. And rather than having a Department of Defense, we have thrown that away also, and put in its place a Department of Offense which no longer fights a foreign foe, but instead, wages war on our countries own people, thus turning our country into a population divided along the lines of ultra-rightwing fascists vs. ultra-leftwing socialists;

Our parents (and now those of us who are nearing the end) are an anomaly—We were not supposed to live as long when the Social Security System was established. We, too, are now an unaffordable social liability, which given current political ideology, must be cast adrift to save those we produced, many of whom have become despicable reminders of our own selfishness—the nut not falling far from the tree.

We take pleasure—that vaporizes with every rising sun—in what is unwrapped but are suffocated by the tossed away wrappings. We enjoy luxuries never even imagined in previous centuries. Yet, we are breathing in toxic fumes; roasting in unbearable heat; can’t drink the out-of-the-tap water that may poison us; living in the residue of devastating hurricanes and floods, which require massive amounts of new capital—at a point in time when our financials reserves have been depleted to the point of zero—to repair, and improve lost infrastructure, to meet an ever-growing threat, that we cause ourselves;

Combatting diseases with a diminishing supply of antibiotics, that will be made by companies run by those who desire, and enshrine, maximum profits at the expense of lives;

Selfishly spreading a virus because we have lost a sense of the value for others but instead value only ourselves—all these, and more, residues of manufacturing to meet the demand that stems from too many consumers living with such luxuries, which never quench their greed, leaves them with a sense of despair, and the throw-away products they have produced, do not fill their felt sense of emptiness.

We made a bargain with the devil and love one side of the bargain but hate the other side. In our inability to look at the consequences of our choices we have created a monster scenario of us destroying us. We are no longer human citizens but rather exclusively in-human consumers—using and throwing away.

We are like the insurance salesman in The Truman Show who discovers his entire life is actually a television show, yet we have not discovered our charade. Instead, we remain proud, unaware, never satisfied, selfishly ungrateful, and inclined to throw a parade to celebrate our genius, but be sure it does not last too long, for fear we will be late for watching a favorite movie (which we have seen ad—infinitum to the point of utter boredom) or our favorite reality TV show, with casts of robotic-idiots, acting in roles of archetypal halfwits, as role-models for the ready-to-be-hooked fish who love the taste of snakeoil.

We have collectively become nothing more than that reality TV show with a reality TV show host as our leader. We have forgotten who we are and have not heeded the advice of the Dalai Lama: “Our prime purpose in this life is to help others. And if you can’t help them, at least don’t hurt them.” There is no “them.” There is only “us,” and we are destroying ourselves, all by ourselves. In the wisdom of Pogo: We have met the enemy and he is us.

Tuesday, September 3, 2019

Lessons from a hurricane—The great paradox.

| Things are not as they appear, nor are they otherwise. |

Complacency and apathy are indeed comfortable. These attitudes lull us into the illusion that all is well when the wolf is near our door. Disasters may fall upon others but not us. Just when we think all is well, the storm of change comes upon us.

We so wanted the security of eternal bliss, but it rushes suddenly away like a hurricane through our fingers, ripping our pleasure apart and leaves us with a devastated spirit. All spiritual traditions address this looming catastrophe, yet we assume it won’t happen to us. In 1 Thessalonians 5, the Apostle Paul wrote,

“…for you know very well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. While people are saying, ‘Peace and safety,’ destruction will come on them suddenly, as labor pains on a pregnant woman, and they will not escape.”

What is this “day of the Lord?” Many would argue it is the final day of reckoning when we must stand before God and be held accountable for our actions. Judgment seems to be the ultimate form of justice that will at last prevail, or so we’ve been led to believe. However, there is an alternative that is worth considering.

An aspect of being human is to think that our way alone is secure while all others are in jeopardy. There is a psychological term to explain this. It’s called either optimism or normalcy bias and is central to the nature of self-destruction. While in such a state of denial, we justify our choices because of our self-centered sensed need. Destruction is someone else’s problem, but certainly not ours. A viral pandemic will strike others, but not us. Our attitude is governed by a self-understanding that appears to keep us apart from others, secure in our sense of superiority. Today there are many who choose to live in states of denial, and they will discover too late that, contrary to belief, they are not apart. What we choose collectively affects us all, and this is made clear when amid a hurricane that indiscriminately rips everything apart.

While in such a state of mind, we are sure that, given our sense of self as unique and special, we are above the suffering of others. But all too often, we make choices we are not proud of because we misidentify as someone unworthy, far beneath the unrealistic standards of perfection we set for ourselves. Or we may do the opposite and imagine that we alone are superior. The moment we awaken from our sleep of self-centered ignorance is our personal day of reckoning, our “day of the Lord.” At that very moment, we discover that we are no more special than anyone else, yet they and we are pure of heart. Before that moment, we lived in a state of complacency and delusion, sometimes called normal.

The very first of the Buddha’s Four Nobel Truths explains the nature of suffering, and it has three aspects:

- The obvious suffering of physical and mental illness, growing old, and dying;

- The anxiety or stress of trying to hold onto things that are constantly changing; and,

- A subtle dissatisfaction pervading all forms of life, because all forms are impermanent and constantly changing.

The second of his truths is that the origin of suffering is craving, conditioned by ignorance of the true nature of things (most particularly ourselves). The third truth is that the complete cessation of suffering is possible when we unveil this true nature, but to do that, we must first let go of what we previously thought. And the final truth is the way to this awakening: the Eight Fold Path. What we discover along this path to a higher level of consciousness is the same driving force of suffering that moves us out of ignorance and towards awakening: the first truth. It is both the cause and the compelling force of change.

“Things are not always as they seem; the first appearance deceives many.”—Phaedrus, circa 15 BCE

Labels:

attachment,

awaken,

bliss,

causal linkage,

clinging,

conditional,

craving,

crisis,

ego-centric,

eight-fold path,

emancipation,

enlightenment,

fear,

ideologies,

Ignorance,

perfection,

reality,

transformation,

wisdom

Sunday, August 11, 2019

Birds of Paradise.

|

| The natural way. |

A recent blogger said she was tired of waking up to the litany of gloom and doom economic news but instead has been taking refuge in the simple recognition of migrating birds. I find this perspective refreshing.

It’s so very easy to fall into a reactionary mindset of what comes our way. On the one hand who can deny the harsh result of billions (if not trillions) of dollars being drained away reacting to one crisis after another— that we create? Lives are being destroyed. On the other hand, all is well. How is it possible that such polar opposites could co-exist? Without diminishing broad-spread mortal suffering I would like to provide some insight.

Birds fly south when they deem a changing of the season, and north when it goes the other way. They do this without recognition of economic news either good or bad. Migration has been happening since the dawn of time. Animals and people move when necessary. It’s a natural way.

This natural way puts the expression “bird brain” in the most different light. The unnatural way is to first create conditions that prompt a survival mode to move (e.g., wars, violence, the devastation of means to exist such as global warming, withdrawal of support to nations that won’t do things our way, trade wars that destroy jobs—on both sides) and then build walls to stop the natural way to move.

A dog will not live in the same space where they defecate, yet we humans seem determined to so destroy our habitat it is turning into much the same thing. There are times when it seems we humans are the most brutal and stupid of all creatures!

Every day the sun rises and sets without consulting our opinions, judgments, or the news. And it’s a good thing. Think about what would happen if this was not so. Maybe the sun would rise (or not) dependent upon our mood that day. Maybe birds would fly south, or not, dependent upon economic ups and downs. If life depended, we’d all be in deep trouble since we never seem to agree on anything. We are enslaved by our differences and the results of those enslavements. We are attached to the way things should be and ignore the way they are and that creates very big difficulties.

Where is it written that the stock market always moves upward? Who says that goodness is perpetually inevitable? Where is it written that those we love will always move in directions we think they should? That one vector continues without fail? These fixed ideas (and our attachment to them) is what creates euphoria and fear, which in turn creates the ups and downs. Life is change. Birds know this and we don’t. There is a season for flying south and another for flying north. Seasons change and we need to adapt. Yet we don’t. Why?

The answer is ego possessiveness and attachment (to what we desire) and resistance (to what we repudiate). We go by way of what we see and ignore what we can’t. Birds don’t do that but we do. What we see is either beautiful or ugly (on the surface) and we respond to such appearances. If we were wise we’d notice that even our own forms are in the process of decay but our true nature is eternal.

The truth is that there was a time when I was a mortally handsome fellow and now I’m just a decaying and wrinkled bag of bones. Does it matter? Not a whit! Nobody gets out of here mortally alive anyway. It happens to us all. What can be seen will always fade but what is eternal and immortal never fades. Paradise is either here and now, or it isn’t. It all depends, mortally. And it doesn’t, immortally.

Labels:

aggresion,

attachment,

circumstances,

clinging,

conditional,

craving,

desire,

divisive,

emancipation,

eternity,

fear,

feed-back,

Ignorance,

insecurity,

liberation,

Perpetual,

relationships,

sharing

Monday, July 15, 2019

Q and A: Beyond Boxes

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia“Thinking outside the box”—A familiar expression that suggests creativity beyond normal limitations. Everyone has heard this expression and in a general way understands the intent. But let’s push this a bit. Let’s do some Q and A outside the box about boxes.

Q: What’s a box?

A: A container within which something exists.

Q: What else?

A: The container establishes boundaries and limitations.

Q: What if there is nothing in the box?

A: It still contains air. Air is not “nothing” but is “no-thing.”

Q: What does that mean?

A: It means that air is not a thing but rather the absence of things and without the absence, it would be impossible to place “things” in the box.

Q: So does that mean that both things (form) and no-things (emptiness) are interdependent?

A: Exactly.

Lao Tsu pointed this out centuries ago yet we dwell on forms and ignore emptiness. Here is what he had to say...

“Thirty spokes share the wheel’s hub;

It is the center that makes it useful.

Shape clay into a vessel;

It is the space within that makes it useful.

Cut doors and windows for a room;

It is the holes which make it useful.

Therefore profit comes from what is there;

Usefulness from what is not there”

Stanza 11—Tao Te Ching

You might ask what value is it to 21st-century people to consider this arcane, centuries-old musing of an ancient Chinese sage? The answer is mutual respect. Every human who has ever lived knows their form and profit but it is rare to find anyone who knows their emptiness (and usefulness).

When we place limits on our form we diminish our potential (usefulness). Profit comes from form; Usefulness from emptiness. We may profit by acknowledging what we know, but how useful are we to ourselves and others when we ignore or denigrate what we don’t know? When we box things in we see them within limitations which we ourselves establish. Space and emptiness have no limits but form does. When we define with concepts we create, we limit both form and emptiness and force ourselves to stay within those limits.

To cherish only what we know at the expense of difference is a violation and diminution of our space and that of others. Why are we so afraid of what we can’t perceive? Why do we fear differences? Why do we prefer boxes and limitations when we can have infinity?

Is it that we have no eyes to see or ears to hear? A box is useful when we acknowledge both the contents and the context and it matters little whether the box belongs to us or another. In any event, immortal space is shared space; only mortal form limits and changes. Genuine emancipation happens when we can release our attachment to mortality and embrace the emptiness of immortality, without confining it to conceptual limitations.

Monday, March 5, 2018

When enough is enough? And the tragedy of perfection.

|

| The surface and the deep |

The idea of life as a journey has merit and deserves thoughtful consideration. A journey begins and proceeds step by step: one step begins, ends, and is followed by the next, which likewise leads to the next until the journey ends.

Each moment proceeds in the same fashion. With foresight, patience, and endurance achievement is possible. The great tragedy is expecting perfection with each and every step. In a way each step is perfect; it is enough (for that moment).

The Buddha said, “There are only two mistakes one can make along the road to truth; not going all the way, and not starting.” The starting has much to say about the motivation to go at all. Many have no hope. Others become complacent with their bird in hand. Some expect magic of the divine, and still, others lack confidence and fear the risk of the unknown.

It is indeed somewhat terrifying to leap into the unknown when all seems well; when we have ours and others don’t. It is human nature (unfortunately) to take the unexpected treasure we’ve found and run, leaving others to find their own. However, if we are the one who lives in misery and have not yet found that treasure, the story is different. Then the motivation changes from satisfaction to a desire for the hidden treasure others have found, and we have not.

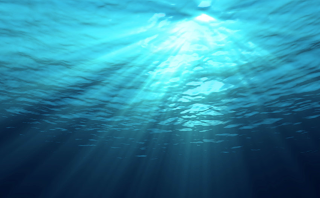

For most of human history the masses have lived in misery without ever having leaped into the great sea of the unknown; the sea where “things” morph into “no-things:” the only realm where true satisfaction exists, ultimate wisdom and truth reside. The two realms of things and no-things coexist, one upon the other, yet the misery of conditional life remains the province of the known, where truth is a variable bouncing like a ball on the waves of that great ocean. Beneath; deep beneath the waves of adversity is the calm, the tranquil, the root of all that exists above.

“All mortal things have a beginning, and an ending.” Each step, each moment, every-thing; All things are enough; all things are perfect, and yet all things exist together, resting upon the deep of a nothing, which is no mere nothing; It is everything.

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

The Deep

The easiest thing in the world is to get swept up in the waves of adversity. During such times it is nearly impossible to keep your cool and not panic.

Over time it is quite possible to learn how to use these waves like a surfer uses a surfboard. It is unreasonable to think we’ll ever find times without waves—It is the nature of life that they come.

Even during tumultuous times, there is calm and tranquility just a few meters beneath the surface. In fact, waves are just the result of the ocean calm being pulled by external forces and without being connected to the deep there could be no waves. The deep and waves are two aspects of what makes the ocean what it is.

Our human challenge is to find that deep place of calm so that during the storms of life we won’t be swept away.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Small steps.

Often, I’ve found myself faced with seemingly insurmountable challenges and felt as if I needed to swallow the entire ocean in a single gulp. The only result of that approach was fear, inaction, and coughing up the imagined impossibility.

But after failing, I came to my senses and remembered an ancient bit of wisdom offered by the Chinese sage Lao Tzu, roughly 2,600 hence.

“Do the difficult things while they are easy and do the great things while they are small. A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.”

The words of Lao Tzu are as useful today as they were a long time ago.

A friend sent me a link to words of wisdom offered by the oldest living person. He just happens to be a Zen man and offered similar thoughts concerning a healthy life. They are worth your time reading. I confess to having a problem with one of his tips: to have no choices but rather accept everything as it comes.

Like everything, the tip has two sides. One side is the peace that comes with feeling the smooth caress of the winds of change on your face in the coolness of the morning breeze. The other side is to get out of the hurricanes of life before devastation occurs. Those are the two sides spoken of by Lao Tzu in the first sentence of the above quote.

Knowing when to stay and when to leave takes art and experience, and both this ancient sage and the world’s oldest man agree, as I do, that breaking down giant challenges into small pieces makes for manageable tasks. Importantly is that first assessment of staying or moving. To inform that assessment, we can turn, not to an ancient sage, but rather to Mark Cane, the contemporary American climate scientist who advises,

“The first step toward success is taken when you refuse to be a captive of the environment in which you first find yourself.”

Regardless, there is always the first, small step or sip of water. Picking and choosing, as well as the wisdom of recognizing our self-imposed captivity, are seeming contradictions, but that is the true nature of Zen: To hold no fixed perspectives but rather use expedient means—upaya-Kausalya, measured and dictated by unfolding and unanticipated circumstances. How very different such advice is from the embedded and rigid ideologies of today.

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

Simple complexity.

I’ve been a student of Zen for more than 40 years. During that time I must have read hundreds of Buddhist and Zen books. To be honest nearly all of them were profound yet abstruse.

Transcendent truths can be perplexing for a number of reasons. Since language is limited and reading is language-centered, this constrains understanding of changing time and cultures. It’s an oil and water conundrum. Additionally, what is considered truth is a variable depending on a host of changing conditions. Mining profound treasures involve a lot of digging and dirt tossing. And after the mining, you still have a problem: How to transmit the gold to others.

Long ago Lao Tzu addressed this problem when he said, “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” That is indeed a perplexing communication challenge. As I’ve worked through this challenge I have struggled to distill and shift out the dirt so that I could speak simply of matters that are anything but simple and obvious.

I’ve studied the writing of the great sages and seers to understand their wisdom. Jesus chose to speak in parables. The New Testament is full of his parables. The Buddha chose similar methods. Both were so erudite their own disciples rarely grasped their insight. And while these methods worked with some, the vast majority still didn’t understand. Life’s greatest truths are not so evident. I’m no sage but I use their communications methods since I am persuaded that if I can find ways to share the wealth of my own mining then a lot of people can begin to find their own treasure.

One of the most valuable communication tools used by The Buddha is known as “Upaya” — expedient means. The principle is simple: Teach people at their level rather than your own. This method is extraordinarily wise. Imagine what would happen in a Kindergarten class if the Ph.D. teacher tried to teach nuclear physics by employing high-level jargon. It doesn’t mean that young people one day won’t be capable of becoming nuclear physicists. But there is a huge difference between knowing something and being an effective teacher. All of us have experienced both and all of us prefer good teachers.

What I have chosen to do is adapt. I use, as much as possible, simple language with graphics and other devices that aid in the learning process so that matters of great profundity can be grasped by people not yet schooled. They know precisely the nature of their own dilemma but they don’t know the nature of the solutions. Transcendent truths provide the solutions they seek. It is my job to speak simply of these truths. All I do is haul water to thirsty horses. The horses decide if they want to drink.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Looking where it’s not

|

| Where is it? |

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name. The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth. The named is the mother of ten thousand things. Ever desireless, one can see the mystery. Ever desiring, one can see the manifestations.”

Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

A question to the Buddha: “What is that smoothers the world? What makes the world so hard to see? What would you say pollutes the world and threatens it the most.”

The Buddha’s Answer: “It is ignorance which smoothers,” the Buddha replied, “and it’s heedlessness and greed which make the world invisible. The hunger of desire pollutes the world, and the great source of fear is the pain of suffering.”

Nipata Sutra

These two points to a central and valuable truth: Desire affects our ability to see clearly. Lao Tzu says that we see the mystery of our being beyond names. In a state of desire, we see manifestations of what can be named. In other words, we see what we want to see, not what’s there. The Buddha said that desire pollutes the world, and ignorance smoothers it. After that, we are lead to greed and heedlessness (e.g., attributes of the ego), which renders the world invisible.

Obviously, the world referred to by Gautama is not the world the average person sees. They see a world manifested from the desire of the ego. We see what we imagine will deliver the object of desire—fulfillment. But suppose, just for the sake of being contrary, that the unseen world is already full, but because we misdiagnose the disease (dis-ease=dukkha), we think it is not full. Now we’re faced with an impossible dilemma: Trying to fill what is already full.

This is a profound paradox that illustrates the driving force beneath the problems we are confronted with every day. We think we are fundamentally incomplete and all the while we are complete. What can be insane than that? It is like a person searching everywhere for the nose on their own face. Without a mirror, we just look right past our own noses. Without finding our worth within, we go looking far and wide, while all the time, what we seek is already in our hands. No, desire means we think we are not already full, yet we are.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

The Bumping Game

There are no formulas, no prescription, nor a set of rules, which stand alone as sufficient to ensure fulfillment or realize our potential. The hope of all humankind is the same—to find our way, to make sense of our existence, discover the means whereby we can make a difference, reach the end of our days and say with honesty, “I did my best.” To simply eat food, grow fat, and move toward the end without examining our own life, as it is lived, rather than the way we think it might have been, is an utter waste. In such a case, we have ignored the ever-present voice that calls to us: “Who are you, and why are you here?”

None of us can live a life of abstraction or fantasy, even though what we imagine our reality to be is nothing more than an illusion we mistake for substance. Yet it is also the only reality we’ll ever have. Most all of us mistake this life of conditions as the sum total—all that exists. Others more fortunate understand life as the conditional and the unconditional. And a rare few go further and see these two as united, beyond our rational capacities. Such people enjoy peace, which passes all understanding because they have experienced no separation between one dimension and another.

Their lives are the lives of others as well as their own. They experience the ever-changing joy and agony of their fellow humans. In their bones, they know the true meaning of compassion and wisdom not as matters of an isolated individual who has constructed a philosophy or theory, which they propose as a one-size-fits-all recommendation. Instead, their knowing gets patched together one moment at a time. They flow like water rather than fixed like a stone.

We come into this world with no answers, not even aware of the questions. Then we begin. We move. We bump into life, and it bumps into us. We fall down. We get up. We’re hungry, and we seek food. Thirsty, we seek water. We are besieged by moving objects as if we were cueballs on a pool table. We remember and think to ourselves, “How can I avoid that?” or “How can I repeat that?”. We project, we plan, and the bumping continues. “That didn’t work. Try a different approach.” Then we try that different approach, and it too fails, or it succeeds for a time only to fail again—the cycle repeats. We learn, adjust, and adapt, or we become crusty, stodgy, and stuck.

The rulebook didn’t come along with our birth, and even if it did, there could never be a book that worked very long in this bumping, changing world. Clearly, there are no answers so long as we stay transfixed and wedded to the movement. The clue should be evident: The problem is seeing without clarity. The solution is seeing clearly. But it isn’t the ordinary seeing that matters. The ordinary way is the problem. The ordinary way leads us into further problems of bumping and getting bumped.

It is what we don’t see that matters, not what we do. What we don’t see has no movement. We see movement, we respond and try to either get out of the way or gravitate toward a moving target.

Why do we care? What compels us toward one moving target and away from another? Why not stand still and let others do their own the bumping and getting bumped? It’s worth looking into and what we discover upon examination is that we either crave what attracts us (trying to retain it) or resist what we find repugnant. But why? What part of us needs, desires, and tries to avoid? Are we experiencing anxiety, fear, and incompletion? Is that what this is all about? Yes, it is. It’s seeing what’s here, and the presumption of insecurity and incompletion that drives the bumping and getting bumped.

So seeing what moves is the problem. Seeing what doesn’t is the solution: Seeing both the seen, the unseen, and understanding which part of us is experiencing the perception of problems where none exist. And once we understand that great matter, then it is time for the rest: Seeing the one doing the seeing—The unseen seer; the one always doing the seeing, the one who doesn’t move, allows movement and engages in the bumping game. Why? To tire of getting bumped and bumping so that we can discover the bumper.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Getting out of jail

Having a clear understanding of a problem is essential to finding a solution. Buddhism may be the best solution to the problem of suffering. But is that the problem or a symptom? Perhaps we need to better understand the root of suffering before accepting it as the problem.

Certainly, illusion is part of the root. An illusion is, of course, something that has no self-containing substance and is fleeting. That is how the four “dharma seals” are defined—All compounded things are impermanent, all emotions are painful, all phenomena are empty, and nirvana is beyond extremes. More to the point, illusion is the sea in which we swim. We think we live in an objectively substantial world. Still, both the Buddha and modern science say otherwise—That our only ability to discern anything is a matter of images projected in our brain. This nature of illusion is foundational to our existence. Consequently, the root problem must be understood within that all-pervasive context. We are idea people living within the framework of ideas. Or, as the Sutra of Complete Enlightenment says, “We solve illusion by employing illusion.” There is no other way.

Then we come to the matter of self-understanding. How did we get here? And where did we come from? That is not a metaphysical set of questions. It infers the emergence of identity and the process of identity formation. And to understand this process is enlightening. All of us begin life in the cocoon of our mother’s womb, where we are a single being and literally attached. At that point, there is no separation between mother and child. There is no such thing as an idea of a separate self since we are not a separate being. Only following mortal birth are we separated, and only then does the process of individuation begin.

Watching a young child begin to grapple with not being one with the mother is an important part of understanding the root problem. Slowly a child becomes self-aware, not as joined physically with mother, but as a separate person with an emerging and isolated identity. At first, this awareness results in stark terror! One moment mother is there, and the next, she is gone. The unavoidable awareness is separation and difference, and then the next step of psychic construction takes place: If not, mother, then who? This moment is the beginning of the idea of self (ego). From that seed grows fear of survival as a separate and isolated individual with a unique but vulnerable identity.

Phenomenally, mutual discretion is the standard. We see others as mutually discrete from us. We see ourselves as separate and apart from them. In our perceived isolation, we are afraid of dying and trapped in a conundrum: We must emerge as independent but are, in fact, linked, if not physically (as previously with mother), then certainly spiritually and mentally. And the result of this conundrum is possessiveness and greed, the rationale being that if we are separate and isolated, then for survival, we must hoard and insure against risk. It quickly becomes a matter of me and mine and self-absorption.

This idea of self—an extension of our ground of illusion—then becomes the mask which hides our truth: That we are not an objective image, but rather a subjective reality that has never been disconnected from anyone or anything. At the imperceptible level of our true nature, we are interdependently connected, but for this awareness to evolve, the image of a separate self (ego) must pass away.

The death of a self-image is a suffering matter since it seems so real (just like all illusions can). Thus, the solution is to dissolve this phantom and find our true, never-divided self—To release our attachment to an idea and find our substance. And that is what makes Zen nearly magical because it is a process of releasing from illusions but always from within the illusion context. We are not “just” an idea. We are both an idea (phenomena—discernible but unreal) and noumena—real but imperceptible. We will never be released from an ego. It is our imaginary self and a part of who we are, but we can be detached from bondage, which comes from seeing ourselves as its exclusive prisoner. From that understanding comes freedom—That we exist and that we don’t: The Middle Way.

Labels:

attachment,

death,

ego-centric,

emancipation,

essential nature,

fabricate,

false self,

fear,

Identity,

imaginary self,

Middle way,

Objectivity,

perception,

personality,

release,

self-image,

Suffering

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1cf616e9-49a3-43a8-a82e-40180743e5d7)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7f4ef62a-e6cd-483f-af79-bc63735d8fb4)