|

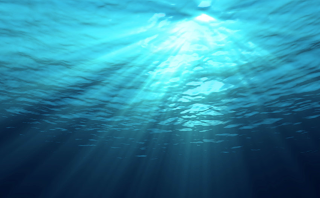

| The surface and the deep |

Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Showing posts with label bliss. Show all posts

Showing posts with label bliss. Show all posts

Monday, March 5, 2018

When enough is enough? And the tragedy of perfection.

Each moment proceeds in the same fashion. With foresight, patience, and endurance achievement is possible. The great tragedy is expecting perfection with each and every step. In a way each step is perfect; it is enough (for that moment).

The Buddha said, “There are only two mistakes one can make along the road to truth; not going all the way, and not starting.” The starting has much to say about the motivation to go at all. Many have no hope. Others become complacent with their bird in hand. Some expect magic of the divine, and still, others lack confidence and fear the risk of the unknown.

For most of human history the masses have lived in misery without ever having leaped into the great sea of the unknown; the sea where “things” morph into “no-things:” the only realm where true satisfaction exists, ultimate wisdom and truth reside. The two realms of things and no-things coexist, one upon the other, yet the misery of conditional life remains the province of the known, where truth is a variable bouncing like a ball on the waves of that great ocean. Beneath; deep beneath the waves of adversity is the calm, the tranquil, the root of all that exists above.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Inherent goodness.

Labels:

bliss,

Buddha nature,

Buddha Womb,

compassion,

Dharmakaya,

emancipation,

essential nature,

eternity,

false self,

Ground of being,

Is-ness,

Middle way,

One Mind,

samadhi,

Self realization,

selfless,

soul

Wednesday, January 22, 2014

Is that all there is?

“Is that all there is? Is that all there is? If that’s all there is my friends, then let’s keep dancing. Let’s break out the booze and have a ball if that’s all there is.”

These words might very well be the mantra for today. They were however, sung by American singer Peggy Lee and an award winner from her album in November 1969. When your life seems surrounded with corruption it is easy to become disillusioned. Peggy Lee’s song was written by the team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller and based on the existential philosophy expressed at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th-century.

More specifically the writers borrowed the idea from the 1896 Disillusionment written by Thomas Mann who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929. Mann was a big fan of Goethe, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, all of whom, in one way or another saw life as meaningless and were considered either implicit or explicit nihilists.

Without plumbing the depths of consciousness it seems logical that life is indeed meaningless. The words of the song keep changing but the message appears to be the same. Even among mainline Buddhism that message was first resonating with what was known as “The Three marks of existence.” The Buddha was thought to have taught that all beings, conditioned by causes (saṅkhāra) are impermanent (anicca) and suffering (dukkhā) while he said not-self (anattā) characterized all dharmas meaning there is no “I” or “mine” in life.

If that was the end of the matter, Buddhism would more than likely, have lasted about twenty seconds. But fortunately that was not the end of the matter. It took some time for Mahāyana Buddhism to emerge, which told the rest of the story. In Chapter 3 (On Grief) of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra the Buddha taught, about what he called “four perversions.”

He said that the true Self signified the Buddha, the eternal signified the Dharmakaya (the Mind of truth), Bliss signified the lack of dukkhā and Nirvana/the Pure signified the Dharma. He went on to say that to cultivate impermanence, suffering, and non-Self has no real value/meaning. “Whoever has these four kinds of perversion, that person does not know the correct cultivation of dharmas. Having these perverse ideas, their (the lost) minds and vision are distorted.”

When life seems to be characterized by violence, political shark-man-ship, power through money, injustice, a growing wave of corruption, despair, apathy, and hopelessness, it’s easy to wonder, “Is this all there is?” And while we may not yet be able to find our true Selves (which is Sunyata), we don’t need to see life through the lens of a victim. A man who waits for enlightenment before being a balm to others is like waiting for the ocean to warm before taking a bath.

While facing such adversity in the present moment, it may require strength, endurance, and keeping a level head. But of equal importance is the clear understanding that the only way to have better “nows” for tomorrows is by making those betters today. A single match can either ignite a blazing inferno of hatred or light a lamp of love that shines brightness into the darkness. Whatever we do in the never-ending “now” will make our world of tomorrow.

We don’t need to be a Malālah Yūsafzay or an Edward Snowden to make a difference. A single act of kindness in whatever sphere we live turns adversity into joy. A single drop of rain waters 10,000 pines.

Sunday, September 25, 2011

The Key to Fulfillment

What you’re about the read now is the result of having lived through extreme adversity, finding victory, and then looking back to find a rational explanation.

What I write about here is that rational, rearview perspective. I never saw this view from the other side, which is to say while in the midst of anxiety. The vision presented here is a retrospective.

If you study Yoga or Buddhism you’ll learn a lot about a unique perspective about why people suffer and you can sum up the entirety of this perspective in one statement: “We suffer because we don’t have a proper grasp of what genuine reality is.”

Usually the response to that summation is MEGO (My eyes glaze over). Everyone who has ever lived, or will ever live, begins with the unchallenged assumption that they know precisely what reality is. They can’t explain it. They just know in some unexplained way. If pressed we can come up with a few dimensions to frame our understanding. Such dimensions as tangibility, mutual discretion and measurement are ordinarily candidates for a definition. In other words if we can perceive stuff, that measured stuff is real. But hardly anyone thoroughly examines the relationship between that understanding and suffering. We measure stuff and people suffer—two observations, and these appear to have nothing to do with each other.

There was a man who devoted his life to a thorough examination of this matter and the world has never been the same since, at least for those who take the time to consider what he discovered. The man lived a long time ago (more than 2,500 years ago) and his name was Siddhartha, who became Gautama Buddha. What he discovered changed my life and the lives of millions since he lived. His understanding is contained in the first of eight steps which he identified to enable anyone to find a way to solve their own suffering problem, and that first step revolves around the interrelated matters of emptiness and dependent origination—my topics for this post.

To the ordinary eye, these two matters are obscure and foreign, but when looked at carefully the way forward becomes clear. The first of these—emptiness—challenges the premise of mutual discretion: that things are different and independent from other things. For example, we regard “up” as different from “down” and are persuaded that these two are independent matters. The same goes for in/out, forwards/backwards, or anything else, which have two opposing dimensions (everything does).

To the ordinary eye these are always separate and opposite, just as Republicans and Democrats are—separate and opposed to one another. Emptiness says simply that this observation is both true and not true at the same time. It is not true that any pair can be divided. Instead these exist only as pairs. Without up, there could be no down. Without an “in” where would “out” be located? Each half of these pairs is not real by themselves but real only as pairs. To acknowledge the validity of one half you must accept the validity of the other half, otherwise neither is valid. Here the rule of discrimination governs all. It’s an either/or world of compromised choices with clear winners and clear losers. In a nutshell that’s emptiness. It goes much deeper than the nut but for the moment just stay with that.

Then we come to a kissing cousin of emptiness—dependent origination. This principle says that everything is linked together (just as the pairs are) and one thing causes another, which then cascades onto other things. The water cycle is a perfect example. Every aspect of this cycle is created by what came before and then creates the next step in the cycle, in a circular feedback that never ends. So long as we remain in the sphere of relative and conditional life none of these feedback cycles can ever be avoided because everything is in constant motion. When one dimension comes into existence what follows also comes into existence. Rising, heated water vapor ultimately cools and turns into rain. Birth ultimately turns into death. These cycles repeat endlessly without a beginning and without an ending. In a nutshell that’s dependent origination.

In our physical and conditional world, these two matters—emptiness and dependent origination point to why we suffer. We do so because we try to retain the good parts of these changing cycles and avoid the bad parts, but this is impossible to orchestrate. What brings us joy in one moment brings us sadness in the next. Nobody can stop the tides of anything, thus the conclusion that “life sucks.” And if that were the end of the matter then that conclusion would be correct. Fortunately that is not the end of the matter because emptiness and dependent origination are deeper matters.

The law of these two principles, if valid, would have to apply to everything including conditional life. Just as up can only exist with the partner of down, conditional life can only exist with the partner of unconditional life. Conditional life is empty by itself and real only with a partner. We can perceive anything and everything of conditional life because of the perceptible nature of objects, and these objects are always in opposition and in motion. The first and preliminary part of solving the suffering problem is thus to not cling but rather to savor each passing moment with the awareness that soon the savor will turn into the sour. Be here now is a familiar code for one form of Zen, but frankly, that premise sucks. Who truly looks forward to eventual sadness? It helps but it is insufficient.

Ultimate victory comes by moving beyond the conditional and into the unconditional where discrimination and sadness cease to exist. What brought me enduring grief was this cycle of destruction. I was trapped in one cycle after another and could find no relief. I never realized until I reached the end there was an alternative. Only when I ran out of gas did I say to myself, “To hell with this,” if I can’t find a better way I don’t want to live.

Then I just sat down and refused to get up until I found the key. Only when I let go, completely, of the bargain of hope did I find the other side—the unconditional side, which I never knew existed. When it happened I was dumb-founded and wholly disoriented, but I was also in a state of mind without suffering! I had no idea what had transpired but I loved it. Before it happened I was full of despair. Afterwards I was whole and pure. But since I had experienced nothing but the cycles for my entire life, I kept waiting and expecting that blissful experience to pass away. It never passed and has remained a constant presence. It’s now been more than 40 years and it is still here.

Having said that, it is important to say that I’m still just as much affected by the swings as before. But no longer do the swings affect my stability. My true sense of being is now rock solid. Nothing causes it to waver. And this is what dependent origination means at the deeper level. Both sides are true together and neither side is true separately. And at a deeper level yet, is the ultimate value of Gautama’s understanding—his first step (Right View): while all of us are different, we are also the same, and neither of these truths is real separately. Conditionally we are apart. Unconditionally we are united.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Ego Death

From time to time, I’ve written about “ego death” or “allowing the self to die.” In Jungian psychology, ego death is synonymous with psychic death, which refers to a fundamental transformation of the psyche.

Our mind is an amazing biological fabrication composed of different cells and neurons located in different parts of our brain, which function differently, yet results in a seamless view of the world and ourselves. In a balanced way, our right and left hemispheres function to bring together very different modalities to form a balanced world view, which is both analytical and compassionate. Unfortunately, most of us are not balanced due to various reasons and tend to be either overly analytic or overly affectively sensitive. For the most part, our left brain rules the day, and this hemisphere is the home of our ego (sense of self).

Our ego-mind perceives the world in a possessive/resistant way, which creates attachments, clinging, and judgments. If we like (a judgment) something, our ego attaches favorably. If we dislike (a judgment) something, our ego attaches unfavorably. This clinging to conditions results in a brittle, judgmental, and inflexible perspective of ourselves, others, and life in general. Whereas a balanced mind recognizes our interdependent union with all life, our ego-mind denies this and treasures exclusivity and independence.

The three poisons (e.g., greed, ignorance, and hatred) manifest out of this imbalanced ego exclusivity. As we grow and mature, these poisons create strife for ourselves and others we come in contact with. We respond to this strife in one of two ways: Blame and denial or learning. The first response just exacerbates the poisons, whereas the latter choice moves us to realize they are rooted in our out of balance ego-mind.

Life, in essence, is structured so that we either awaken or we continue to suffer. This alternative set (in Buddhist terminology) is referred to as Nirvana vs. Saṃsāra—Bliss vs. Suffering. If we live long enough and are open-minded, we will eventually come to see the truth, and when this transformation happens, our ego (as the exclusive judge) dies—so to speak. The fact is this sense of self never dies but is transformed.

This transformation can be facilitated through Zen meditation. We learn to quiet the constant left-brain chatter that emanates from our ego with its judgments and critique, which normally overshadows our compassionate nature (e.g., dominates). This chatter is so loud and relentless that we could easily go through life with very little, if any, understanding of our pure and true nature, which makes life worth living. It is unfortunate that few follow this path toward breakthrough and remain ignorant of our complete human potential.

Breaking through occurs when our left-brain chatter comes to a halt, and we become aware of our deepest nature, which is always present. This is a matter of subtraction—a sort of shedding—rather than adding or seeking. Lao Tzu put it this way...“Empty yourself of everything. Let the mind rest at peace. The ten thousand things rise and fall while the Self watches their return.” And this...“In the pursuit of learning, every day, something is acquired. In the pursuit of Tao, every day, something is dropped. Less and less is done until non-action is achieved (e.g., non-action=Wu Wei). When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.”

Labels:

anger,

bliss,

ego,

fabricate,

false self,

greed,

Ignorance,

mind,

Nirvana,

samsara,

Suffering,

zazen

Sunday, January 13, 2008

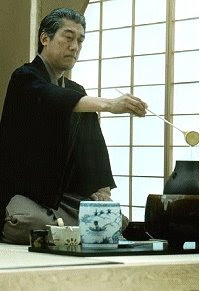

Drinking Tea

In my last posting, I ended with a confusing idea. This “...just go on suffering anyway” idea sounds wrong-headed, so I must explain. Suffering is what is caused by attachment and attachment can’t be avoided so long as we are subject to dependent origination and causal linkage. In my example of a driver and what is driven, combined with a linkage between cars and accidents, the conjunction results in suffering.

The only way to have a different, non-suffering outcome is to detach drivers from cars and create a different causal linkage that doesn’t entail accidents. But this is a purely fictitious/after-the-fact fantasy. In the first place, it is impossible to detach drivers from cars since drivers arise with what they drive (cars) and no one can wind time backyards and change circumstances in a way that may seem more desirable.

The opposite of suffering (bliss) is not something that entails circumstances nor subject/object separation. Suffering and bliss occur in the same realm. Bliss has nothing to do with circumstances. Bliss is unconditioned—transcendent to all circumstances and results from accepting life just the way it is and not being disturbed. And why would it not be disturbing? It would be disturbing—always—at the conditioned level because of dependent origination and causal linkages and never disturbed at the unconditional level. We are not one kind of condition vs. another kind of condition. We are both conditions and unconditions at once.

The truth is that we are not carved up into mutually discrete sections like some butcher shop chart of a cow. We are an integrated whole. We speak as though we are parceled up but that manner of speaking is purely for convenience purposes. The relevant issue is who we are and how we respond to life, not what happens beyond our control (which is most everything). When we identify ourselves with the roles we play or the infinite abstractions of self, we will always suffer because these ways of identifying are not who we are. Who we are is unconditional and always secure. So when the tides of life flood us we will suffer yet we won’t.

We all have relationships. I am both a husband and a father. A husband is a husband because there is a wife. A father is a father because there is a child. When my sense of identity is attached to those roles I am vulnerable and subject to suffering. Why? Because when we have relationships we form conditioned expectations of performance. So long as our relationship partner performs up to expectations everything seems satisfactory. But let circumstances go against our expectations, then there are problems.

We will never find peace when we place our hopes for fulfillment in another person. So long as we do that we’ll be disturbed. The correct way is to get clear about who we really are (selfless and without conditions). Then we can have fulfilling relationships which are filled-full to begin with, not as a result of what our partner does or doesn’t do. It is ludicrous to speak of relationships which are detached. Such a thing can’t exist. Husbands are attached to wives in the same way that drivers are attached to cars. There is no such thing as a husband without a wife. That would be an ex-husband or a widower, neither of which would be a husband. This is what I meant when I said—“When we drink tea, we just drink tea, with nothing added. No honey (thoughts)—just pure tea.”

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

The First Step

The Eight-fold Path is a road map for traveling from suffering to awakening. From a certain perspective, it is about traveling to Nirvana. But from another perspective, it is not a journey since there is nowhere to go from and nowhere to go to. This sounds like double-speak, but it is not. The keyword in these statements is perspective.

Suppose we are at a destination but don’t know. For whatever reason, we are confused. Maybe it is a case that we awaken from a dream into a fog bank so thick that it is impossible to see the nose on our face. In the dream, we imagined that we were at some other place, and when we awaken, we retain this dream. In such a state, we travel out of one dream into another. There seemed like a far-distant destination from this deluded perspective, but when the fog lifts and a new perspective emerges, we realize we have never left.

This is a non-journey or a journey depending on the perspective, either with or without the delusion of dreams and fog. It is important to know our beginning, as well as our destination. In the vast majority of cases, suffering results from being lost in the fog of delusions without realizing that we are already home. We lust for what we have already, but in ignorance, we are like people who die of thirst while in the vast sea of bliss. It is worth noting that to know you’re crazy, you must be sane. And to think you are sane, you must be crazy since you can neither think your way into sanity nor know you are crazy when you are. “A fool who knows his foolishness is wise at least to that extent, but a fool who thinks himself wise is a fool indeed.”

We imagine ourselves in poverty only because we are not aware of our source. In such an imaginary state, we have no ability to harness abundance. Abundance, continuously available through the dharmakāya, can only be accessed through our physical form. And our physical form is nothing without the infinite, always-full, never-ending, well-spring of dharmakāya.

These “aspects” of Buddha-Nature are inexorably joined and glued together through our spiritual aspect. The confluence of these three aspects is known in Buddhism as the “Trikaya”—the unseen/ever-lasting dharmakāya physical embodiment and spiritual dimension. From the perspective of dharmakāya, nothing is lacking. There is no suffering and nothing but the unending bliss of Nirvana. This is the Eight-fold Path destination, yet it has always been with us. Our beginning point for the journey is the dream-state and fog, and it is the task of the Path to remove the delusions which obscure the truth of our existence and allow us to see that we are already home.

Like any road map, it’s important to have the correct perspective or “viewpoint,” which is why the first step on this journey is the Right View. Without the correct view, it will be a case of the blind leading the blind, traveling forever and getting nowhere. From one perspective, this is non-dharma dharma. It is not a truth or teaching since there is no truth lacking, no teaching to be taught, no teacher to teach, and no student to learn. These entities do not exist independently. They are empty of intrinsic substance.

This is the perspective of empty-emptiness—the ultimate non-truth truth. But most of us begin far away from this lofty goal of blissful Nirvana. For us, there is dharma—a partial truth which we pursue so long as the teaching retains merit. When we learn what we need to learn, we must release the teaching, as we must release everything. To embrace dharma is critical. To become attached is death. With one hand, we grasp, and with the other, we let go.

Critical to this first step of Right View is attachment and attaches, the principle of resistance, and one who resists. The Buddha preached a doctrine of non-self and a doctrine of Self depending on the object of attachment and the nature of the one who attaches. Those who concluded that nothing exists were taught the dharma of self. For those who concluded that everything exists, he taught the dharma of non-self. The nature of identity and the object of attachment determined which “medicine” was administered.

In truth, neither self nor non-self exists as independent entities. Both are subject to dependent origination. The self majesty as the Tathagatagarbha (Buddha-womb), the ultimate, non-differentiated source spoken of in the Heart Sutra and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, is one dharma. The impermanent non-self/ego is a dharma that teaches about the other side. Such conclusions as “All conditioned things are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, shadows; Like dew and also like lightning. Thus should they be contemplated,” are central to the teaching of the Diamond Sutra.

There is conditioned reality and unconditional reality. They exist as two book-ends propping up the dharma of dependent origination. Likewise, the premise that nothing exists (Nihilism) is the flip side of everything that exists (Absolutism). These, too, are likewise subject to dependent origination. To cling to one view (or another) at the other’s exclusion is still a form of attachment that perpetuates suffering. To cling to, resist, a non-self (ego) or a self is still attachment. It is not an issue of establishing the validity of one view vs. another view—which will involve never-ending speculation since both are true (dependently) and neither is true (independently). The issue is seeing all views, being rid of all views, and clinging to none.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)