|

| Fabrication? Or real? |

Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Showing posts with label Buddha Womb. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Buddha Womb. Show all posts

Monday, March 20, 2017

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Inherent goodness.

Labels:

bliss,

Buddha nature,

Buddha Womb,

compassion,

Dharmakaya,

emancipation,

essential nature,

eternity,

false self,

Ground of being,

Is-ness,

Middle way,

One Mind,

samadhi,

Self realization,

selfless,

soul

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

To see ourselves truly.

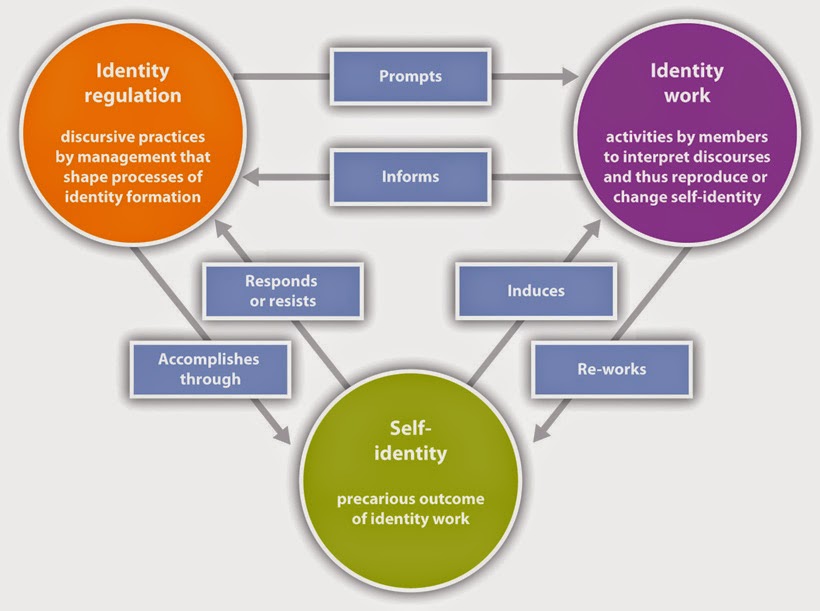

The Scottish poet Robert Burns coined the phrase, “Ahh, to see ourselves as others see us...” and this way of seeing is indeed valuable. However, there is a more valuable way: To see ourselves as we truly are beyond the ordinary lens of perception. What is this strange way?

The Lankavatara was allegedly the sutra most revered by Bodhidharma: the father of Zen. Among the myriad sutras, the Lankavatara lays out the essential challenge inherent in the human dilemma. Here we see how the matter of perception leads us into error. The problem is that the world (including our thoughts) is perceived by-way-of discriminate forms, and we remain oblivious to the one doing the perceiving (ourselves).

We see shapes and forms configured in different ways before us. We hear sounds tinkling or loud. We smell different aromas, and through this manner of distinguishing differences, we form judgments of like and dislike, clinging to the first and resisting the latter.

This process is essential and can’t be avoided, but unless we become aware—deeply aware—of the indiscriminate perceiver (who is beyond all color and form), we become mesmerized and enslaved by the dance of differentiation, all the while creating havoc for ourselves and others. The sutra says the result of this ignorance are minds which “burn with the fires of greed, anger and folly, finding delight in a world of multitudinous forms, their thoughts obsessed with ideas of birth, growth, and destruction, not well understanding what is meant by existence and non-existence, and being impressed by erroneous discriminations and speculations since beginningless time, fall into the habit of grasping this and that and thereby becoming attached to them.”

This unavoidable process leads to clinging to an evanescent world of objects. And as we cling, we oppose the truth of our unknowing and therefore are trapped in karma born of greed, anger and folly. The accumulation of karma then goes on and we become imprisoned in a cocoon of discrimination and are unable to free ourselves from the rounds of birth and death.

The Buddha said that it is like seeing one’s own image in a mirror and taking the image as real, or seeing the moon reflected on the surface of water and taking it to be the actual moon. To see in this way is dualistic whereas to see truly is a matter of Oneness revealed within innermost consciousness.

The unavoidable conclusion of seeing beyond the biased lens of perception is all of us are the same at the deepest level, none better or worse. It is all too easy to become trapped by the constant flow of tidal forces and forget that each of us is the master of our very own sea.

Friday, September 13, 2013

The essence of essence.

|

| The essential essence |

There is a curious correspondence between essential oil and us. We, too, contain an essence that has been extracted from our source, and, like essential oil, this essence contains the aroma of the source. Neither an essential oil nor our ineffable spirit can be further distilled, and neither is subject to changing conditions. Once we arrive at the essence the aroma can be infused in various media and the aroma persists. The difference between essential oil and us is that our source is needed, never goes away, and remains an unchanging aspect, forever.

What is the essence of the essence? Of all essences? Bodhidharma called the essential nature “our mind”—The Buddha, not the “quotidian” mind. This mind is our spiritual essence. Nothing, he said, is more essential than that. It is the void void: The critical spirit. Out of this apparent nothingness comes everything. Nothingness is the realm of the unconditional absolute, beyond the conditions of this or that.

That may or may not sound esoteric, lacking usefulness. Still, I’ll offer you two frames of reference that illustrate extreme value, albeit unseen: One from Lao Tzu and the other from physicist Lawrence Krauss. Lao Tzu said this about usefulness:

“We join spokes together in a wheel,

but it is the center hole

that makes the wagon move.

We shape clay into a pot,

but it is the emptiness inside

that holds whatever we want.

We hammer wood for a house,

but it is the inner space

that makes it livable.

We work with being,

but non-being is what we use.”

And this from Lawrence Krauss. Our perceptual capacities are mesmerized by what moves, captured as a moth to a flame, but we never consider what moves them. And nothing is more useful than understanding that essence.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

The illusion of you and me.

|

| The shadow of self or the reality casting the shadow? |

The tenet of “no self” has been a fundamental, defining loadstone of Buddhism since the very

beginning. The term originally used for self/ego was “anatman” and the contention

surrounding this matter was divided between those who argued for self vs. those

who argued the opposite anatman (self vs. no-self). It boiled down to the issue

of any phenomenal thing possessing an independent nature. Closely aligned with

this argument was the understanding that all things were empty (of independent

essence). In other words, everything could only exist dependently, thus the

principle of dependent origination.

This argument stood for a long time until Nagarjuna came along with his Two Truth Doctrine in which he laid out his understanding of what the Buddha had taught, culminating with the Middle Way which expressed the Buddha’s conclusion of, “Not this (atman). Not that (anatman). Neither not (atman). Neither not (anatman).”

The importance of this conclusion is significant and profound but unfortunately seems to be a broadly unresolved matter. What Nagarjuna said in his Two Truth Doctrine was that there is a difference between the conventional, discriminate view (the common-sense view) and the sublime, indiscriminate view (ultimate truth) and that no one could be set free unless they experienced the sublime.

In the 8th-century an

Indian Buddhist philosopher by the name of Śāntideva said that in order to be

able to deny something, we first have to know what it is we’re denying. The

logic of that is peerless. He went on to say:

“Without contacting the entity that is imputed. You will not apprehend the absence of that entity.” In a similar manner the Lankavatara Sutra (a Mahayana favorite of Bodhidharma) addressed the issue of one vs. another with this:

“In this world whose nature is like

a dream, there is place for praise and blame, but in the ultimate Reality of

Dharmakāya (our true transcendent mind of wisdom) which is far beyond the senses

and the discriminating mind, what is there to praise?”

The wisdom of emptiness and dependent origination ultimately reduces down to there being no difference between form and emptiness. They are one and the same thing: two sides of the same coin. One side perceptible (phenomena); the other side beyond perception (noumena). There have been numerous terms used as alternates for noumena ranging from Buddha-Nature, Dharmakāya, the Void, Ground of being and the preference by Zen and Yogācāra was Mind—primordial mind (not the illusion of mind nor the illusion of self vs. no self). In this state of mind there is no discrimination—all is unified, whole and complete, so there can be no difference between one thing and another thing.

Huang Po (Japanese—Obaku;

9th century China) was particularly lucid in his teaching about these terms. In

the Chün Chou Record he said this:

“To say that the real Dharmakāya (the

Absolute) of the Buddha resembles the Void is another way of saying that the

Dharmakāya is the Void and that the Void is the Dharmakāya...they are one and

the same thing...When all forms are abandoned, there is the Buddha...the void

is not really void, but the realm of the real Dharma. This spiritually

enlightening nature is without beginning...this great Nirvanic nature is Mind;

Mind is the Buddha, and the Buddha is the Dharma.”

The Yogācārians took this to the logical conclusion and stated that everything was mind. You are mind. I am mind. The entire universe is nothing but mind. This, however, did not resolve the matter, and 2,500 years later the issue of atman vs. anatman remains unresolved. The Middle Way remains a matter of contention. Consequently there exist today three kinds of Buddhist practice: The kind that dogmatically clings to self, a second that dogmatically clings to no self and a third that says, “Not atman. Not anatman. Neither not atman. Neither not anatman.”

In the end you will only know when you experience the sublime. Then the argument will come to an end and you’ll never be able to convey your answer. That is the ultimate test, “…far beyond the senses and the discriminating mind, what is there to praise (or blame)?”

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Mixing it up.

We’re a curious species. Being human puts us at the top of the food chain. It also puts us at the top of other chains, such as the chain of creativity. No other life form (at least none that we know of) can imagine and solve problems as we do.

Unfortunately, this seems to be a two-edged sword. One way cuts in the way of creation, and the other way cuts in the form of destruction. We are masters of both.

Awhile back, I wrote an article called a “Bird in hand” and spoke about compounds that result from mixing different things together. The point of that article was that once mixed, an entirely new compound results. The separate ingredients can then no longer be detected, but something new has been created.

I’m an old man now and have been kicking around spiritual conclaves for quite some time, and I’ve noticed a meaningful thing about compounds. People show up in a wide variety of such places for various reasons, but the alleged reason is they go there seeking God. After a time, many remain for other reasons, and they forget about why they came in the first place. A rare few figure out an essential truth: God doesn’t live in churches, synagogues, or temples. God lives in people.

Many people pay lip service to what their own scriptures tell them. For example, Christian scripture says that “You are the body of Christ.” If you happen to be a Buddhist you’re taught that everyone contains the enlivening essence of The Buddha. But too few seem able to accept the resulting compound and just go ahead and act like God is absent from the true temple of themselves.

Have you ever wondered what our world would be like if everyone conducted themselves by embracing this fundamental principle? If we really want to make the world a better place, begin to see yourself and others as a compound container of divinity. I am aware that most of us exhibit some less than ideal nastiness, but it’s also mixed together with genuine love and compassion. Adversity seems to bring out the goodness that is always there. And even if you don’t accept the idea that we are the resulting compound mixture of spirit and matter, it never hurts to pretend that we are.

Labels:

Buddha nature,

Buddha Womb,

Buddhist scripture,

Christian,

Dharmakaya,

discrimination,

emancipation,

essence,

essential nature,

Ground of being,

Holy Spirit,

House of God,

Jesus,

truth,

unseen

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

The rule of what's real?

More than anything else, Buddhism is a practice of reality. What is real? Are things exactly as they are, without addition or subtraction? Or perhaps they are incomplete and need further embellishment and refinements, which we call discrimination.

Do we believe we can refine what is already perfect—that without our ego-centric preoccupations, reality is needful? Within the true mind, all Buddhas, all-everything is complete, pure, whole, perfectly integrated without division and alienation, which we refer to as unity. Nothing within that realm is lacking or needful.

And yet we exist, apparently as separate individuals with no discernable link to other life forms. It is a profound paradox that, on the one hand, seems eminently reasonable and, on the other hand, insane. Dependent origination is supremely flawless. Nothing comes into existence alone, out of nothing. As soon as one thing arises, another arises at the same time. Light and dark arise together. Up and down arise together. Good and evil; strong and weak; man and woman; mother and child; thinking and thinker—everything is originated dependently. Nothing escapes this provision. And yet our rational, thinking mind tells us otherwise.

So what is real: The gilded lily or just the lily? You see, there is the essential dilemma: We are beings who think, reason, and imagine. And these functions are extremely useful in everyday life. But these are just tools we use for abstracting, manipulating, and imagining life. Tools are not life. They are tools.

When we use mundane logic within the framework of the toolset, certain rules apply. One number plus another number equals a particular sum. Two plus two always equals four, and it doesn’t matter if you speak Chinese, Russian, or English.

Mundane logic is universal. When we operate within this abstraction box, we agree to play by defining the box. But there is another form of logic that transcends abstraction and is called “supra-mundane” logic with a different set of rules that contains (but is not limited to) mundane logic. It is impossible to solve certain problems within the abstraction box because of the fixed rules that define its existence.

Take the thinker/thinking problem, for example. How can there be thinking without a thinker who thinks? This problem can’t be solved with mundane logic, and the reason is that both thinkers and thoughts are abstractions—imaginary. If both are abstractions, there is no place for reality to alight. At least one of the two must be real to solve the problem, and when that condition applies, the “rules” of abstract limitations are broken.

And here is the secret: Dependent origination rules, not abstraction. This overriding rule says that abstraction must be balanced with reality. It takes something real to abstract. Abstractions produced by other abstractions are a mirage. A thinker is an abstraction, and a thinker’s product is just an extension of the unreal abstraction. In truth, there is no thinker and, thus, no thinking. Both are the products of the imagination and thus have no permanence. Everything in temporal life is constantly changing.

Reality is understood in different ways. The most popular way depends upon tangible measurability. Physics completely embraces this understanding. A different metaphysical understanding is permanence. From the perspective of mortal life, nothing is permanent and must be seen as unreal. Life as we know it is both temporal and permanent. One aspect is tangibly measurable (form), and the other aspect is permanent yet unmeasurable (emptiness). How can something wholely empty, by itself, be transformed into a form unless it is paired with a form? Abstractions and reality arise together (dependent origination). These are just variations on the theme of form and emptiness. Form is a manifestation of emptiness just as an abstraction is a manifestation of reality. It is reality that is thinking, not an imaginary thinker. This is what Bodhidharma called “Mind essence”—the co-joining of form and emptiness.

“Mind essence” is a challenging notion to wrap our thinking around since thinking is about abstractions, and this “Mind essence” is authentic yet unseen. We lust for forms of reality to put our hands and thoughts around, but the mind doesn’t allow either form of grasping. The odd thing is that we use our minds continuously without defining what, where, or how the mind exists. If we decided, for even an instant, that we wouldn’t think any longer until we grasped the “what, where, and how,” we would be dead in a flash. So we don’t think about the mind. We use the function without knowing how it functions. We don’t need to know how it functions, just that it does.

In the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra the Buddha said we know things two ways: Either through outer signs or through fathoming. To know something through outer signs is like seeing smoke and deducing fire. We don’t see the fire but know it’s there because smoke and fire are linked through dependent origination. It is the same with the mind. We don’t see the mind, but we know it’s there because we use it. This is an example of touching the real through abstraction. To know something through fathoming is to know directly, by-passing abstractions. The first—outer signs—is an example of mundane logic. The second—fathoming—is an example of supra-mundane logic. We don’t know how we know; we know that we know.

So what is real—in the fullest sense? We are here in bodily form. That is an undeniable fact of tangible verification. That’s a part of what’s real. The body is born, grows, becomes attached, suffers, gets old, and dies. That’s a part of what’s real—tangibly verified. What is not tangibly verified is what we can’t see. We can’t see what moves us. We can’t see the mind. We can’t see the spark of life that activates or originates us. We can’t see beyond the grave.

Yet without these unseen dimensions, which we use every moment throughout life, the body couldn’t function and move. How can we deny these dimensions just because we can’t see them? They, too, must be a part of what’s real. Whatever name or names we use to convey and communicate about this unseen dimension is not relevant. “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” We can’t see the fragrance, but it smells sweet nevertheless. This is another way of seeing the unseen.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Core principles

Certain core principles define any human endeavor, and this is true of Buddhism. One of the core principles is dependent origination which underscores nearly all Buddhist thought. Another is impermanence. Another core principle is emptiness, which is an aspect of dependent origination and serves as the basis for the Heart Sutra—Form is emptiness; Emptiness is form.

To many, this equality between form and emptiness is confusing. It seems impossible that perceptible form can be the same thing as emptiness, which is imperceptible, yet the Heart Sutra tells us they are the same. Dependent origination helps us to understand, which says that nothing exists as a mutually discrete entity, separate and apart from anything else. Instead, things arise and cease to exist simultaneously—Rain and water are one; a mother and a child are one. Neither rain nor a child can exist separate and apart from a source. These are just two examples among an infinite set of pairs. The ultimate pair is form and emptiness; Nothing is more fundamental than that—Everything else is a subset.

It would be impossible to separate rain from water or a child from a mother. This is easy to understand. What is not so easy to understand is that all forms are paired with emptiness. Buddhism teaches that all phenomena are impermanent and simple reflection affirms this. Nothing lasts, and clinging or resisting the impermanence of form creates suffering; thus, bliss is not found in phenomenal life. So, where is there a source of hope? Our hope lies imperceptibly beneath impermanence at the heart of decay. And what is that heart? Huang Po (Japanese—Obaku; 9th century China) was particularly lucid in his teaching about this. In the Chün Chou Record he said this:

“To say that the real Dharmakaya (the Absolute) of the Buddha resembles the Void is another way of saying that the Dharmakaya is the Void and that the Void is the Dharmakaya...they are one and the same thing...When all forms are abandoned, there is the Buddha...the void is not really void but the realm of the real Dharma. This spiritually enlightening nature is without beginning...this great Nirvanic nature is Mind; Mind is the Buddha, and the Buddha is the Dharma.”

From Huang Po’s perspective, there is a bonded connection between phenomena and this One Mind—They too are the same thing. Neither can exist apart from the other. Hear what he said about his connection...

“To gaze upon a drop of water is to behold the nature of all the waters of the universe. Moreover, in thus contemplating the totality of phenomena, you are contemplating the totality of Mind. All these phenomena are intrinsically void, yet this Mind with which they are identical is no mere nothingness. By this, I mean that it does exist but, in a way, too marvelous for us to comprehend. It is an existence which is no existence, a non-existence which is nevertheless existence.”

“To the ancients, to find the true essence of life, it was necessary to cast off body and mind. When all forms are abandoned, there is the Buddha.” In an unexplainable way, Mind is no-Mind, which is, of course, the Heart Sutra teaches—Form is emptiness. This Void/Emptiness is the ground out of which impermanent forms arise. It is Buddha-nature (Buddha dhatu—womb of the Buddha: Our essential nature). And the pearl of hope contained in this understanding is that while phenomenal life blows away like dust in the wind, our true nature never passes away. Our intrinsic nature is both natural (phenomenal and finite) and transcendent (noumenal and infinite). We are both form and emptiness. To savor, just the impermanence aspect of Zen without transcendence is to suck on an empty clamshell and imagine a full stomach.

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

The First Step

The Eight-fold Path is a road map for traveling from suffering to awakening. From a certain perspective, it is about traveling to Nirvana. But from another perspective, it is not a journey since there is nowhere to go from and nowhere to go to. This sounds like double-speak, but it is not. The keyword in these statements is perspective.

Suppose we are at a destination but don’t know. For whatever reason, we are confused. Maybe it is a case that we awaken from a dream into a fog bank so thick that it is impossible to see the nose on our face. In the dream, we imagined that we were at some other place, and when we awaken, we retain this dream. In such a state, we travel out of one dream into another. There seemed like a far-distant destination from this deluded perspective, but when the fog lifts and a new perspective emerges, we realize we have never left.

This is a non-journey or a journey depending on the perspective, either with or without the delusion of dreams and fog. It is important to know our beginning, as well as our destination. In the vast majority of cases, suffering results from being lost in the fog of delusions without realizing that we are already home. We lust for what we have already, but in ignorance, we are like people who die of thirst while in the vast sea of bliss. It is worth noting that to know you’re crazy, you must be sane. And to think you are sane, you must be crazy since you can neither think your way into sanity nor know you are crazy when you are. “A fool who knows his foolishness is wise at least to that extent, but a fool who thinks himself wise is a fool indeed.”

We imagine ourselves in poverty only because we are not aware of our source. In such an imaginary state, we have no ability to harness abundance. Abundance, continuously available through the dharmakāya, can only be accessed through our physical form. And our physical form is nothing without the infinite, always-full, never-ending, well-spring of dharmakāya.

These “aspects” of Buddha-Nature are inexorably joined and glued together through our spiritual aspect. The confluence of these three aspects is known in Buddhism as the “Trikaya”—the unseen/ever-lasting dharmakāya physical embodiment and spiritual dimension. From the perspective of dharmakāya, nothing is lacking. There is no suffering and nothing but the unending bliss of Nirvana. This is the Eight-fold Path destination, yet it has always been with us. Our beginning point for the journey is the dream-state and fog, and it is the task of the Path to remove the delusions which obscure the truth of our existence and allow us to see that we are already home.

Like any road map, it’s important to have the correct perspective or “viewpoint,” which is why the first step on this journey is the Right View. Without the correct view, it will be a case of the blind leading the blind, traveling forever and getting nowhere. From one perspective, this is non-dharma dharma. It is not a truth or teaching since there is no truth lacking, no teaching to be taught, no teacher to teach, and no student to learn. These entities do not exist independently. They are empty of intrinsic substance.

This is the perspective of empty-emptiness—the ultimate non-truth truth. But most of us begin far away from this lofty goal of blissful Nirvana. For us, there is dharma—a partial truth which we pursue so long as the teaching retains merit. When we learn what we need to learn, we must release the teaching, as we must release everything. To embrace dharma is critical. To become attached is death. With one hand, we grasp, and with the other, we let go.

Critical to this first step of Right View is attachment and attaches, the principle of resistance, and one who resists. The Buddha preached a doctrine of non-self and a doctrine of Self depending on the object of attachment and the nature of the one who attaches. Those who concluded that nothing exists were taught the dharma of self. For those who concluded that everything exists, he taught the dharma of non-self. The nature of identity and the object of attachment determined which “medicine” was administered.

In truth, neither self nor non-self exists as independent entities. Both are subject to dependent origination. The self majesty as the Tathagatagarbha (Buddha-womb), the ultimate, non-differentiated source spoken of in the Heart Sutra and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, is one dharma. The impermanent non-self/ego is a dharma that teaches about the other side. Such conclusions as “All conditioned things are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, shadows; Like dew and also like lightning. Thus should they be contemplated,” are central to the teaching of the Diamond Sutra.

There is conditioned reality and unconditional reality. They exist as two book-ends propping up the dharma of dependent origination. Likewise, the premise that nothing exists (Nihilism) is the flip side of everything that exists (Absolutism). These, too, are likewise subject to dependent origination. To cling to one view (or another) at the other’s exclusion is still a form of attachment that perpetuates suffering. To cling to, resist, a non-self (ego) or a self is still attachment. It is not an issue of establishing the validity of one view vs. another view—which will involve never-ending speculation since both are true (dependently) and neither is true (independently). The issue is seeing all views, being rid of all views, and clinging to none.

Saturday, December 22, 2007

Seeing the Unseen

In the Diamond Sutra, The Buddha has a conversation with Subhuti, one of his esteemed disciples. In the course of their conversation, The Buddha mentions five different kinds of vision. These same five are reflected in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra.

The five ways of seeing are:

1. The mundane human eye—Our mortal eye; the normal organ with which we see an object, with limitation, for instance, in darkness, with obstruction. There is a viewer (subject) and what is viewed (object) and thus duality.

2. The Heavenly eye —It can see in darkness and in the distance, attainable in Zazen.

3. The Wisdom eye —The eye of an Arhat (an advanced monk) and two others: the sound-hearers (Sravaka: One who hears the Dharma as a disciple) and the (Praetykabuddha: A “lone” buddha who gains enlightenment without a teacher by reflecting on dependent origination). These can see the false and empty nature of all phenomena.

4. The Dharma eye —The eye of a Bodhisattva can see all the dharmas in the world and beyond. With this eye, the Bodhisattva sees the interconnectedness of all and experiences non-duality. He then embraces genuine compassion seeing no difference between himself and every other manifestation of Buddha-Nature. He is in undifferentiated bliss. This is what Sokai-An says is the Great Self—“Self-awakening’ is awakening to one’s own self. But this self is a Great Self. Not this self called Mr. Smith, but the Self that has no name, which is everywhere. Everyone can be this Self that is the Great Self, but you cannot awaken to this Self through your own notions.”

5. The Buddha eye —The eye of omniscience. It can see all those four previous eyes can see.

Complete and thorough enlightenment is to see with the eye of a Buddha, which according to Buddhist sutras, could take many lifetimes, so we should not be dismayed if we don’t leap to the front of the line overnight. What none of us knows is where we enter this stream of insight. We only know how we see, not what we don’t. For all we know, we may have been on the Path for a Kalpa already.

Manjushri is the Bodhisattva who represents wisdom. He holds a sword in his right hand—symbolizing his ability to cut through the delusions of the non-Self. In his left hand, he holds a book—the Perfection of Wisdom teaching on Prajnaparamita, which grows from the lotus: the symbol of enlightenment. On his head is a crown with five eyes—The eyes spoke of above.

Manjushri symbolizes prajnaparamita: the perfection of wisdom. His wisdom is transcendent, meaning that it is divinely rooted and takes shape circumstantially. In the normal sense, rules are discriminated against and governed by duality, administered in a fixed fashion, and rarely reflects justice. Life is fluid and ever-changing. To apply fixed rules in the fluid dimension of ordinary life ensures conflict. Precepts are both the letter and the spirit of the law. The letter defines within the framework of form and spirit undergirds the form with essence/emptiness.

Nagarjuna referred to these as two aspects of a common reality, which he labeled as conventional and the sublime. The Buddha said in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra that while his true nature is eternal and unchanging (e.g., sublime), he takes form and adapts his shape (e.g., conventionally) according to specific circumstances as needed “To pass beings to the other shore.” In one case, he may take the form of a beggar or a prostitute. In another, he emerges as a King.

Whatever specific circumstances exist, The Buddha transforms to meet particular needs to emancipate those in spiritual need. It is The Buddha who implants the seed of inquiry, which compels those spiritually ill to seek the Dharma. This explains the motive to action, which many experiences. It is an itch that seeks relief and nags us until we resolve our illnesses. Manjushri is the moderator of the fused realities of form and emptiness. His wisdom comes from beyond but is applied materially, just as Bodhidharma’s Mind determines motion. The throne upon which he sits in the lotus depicting the source of his power.

That explanation accounts for the metaphysics of seeing the unseen. The depth of that seeing is a function of advancing capacity, which is a measure of our success in eliminating delusions. The URNA (a concave circular dot—an auspicious mark manifested by a whorl of white hair on the forehead between the eyebrows, often found on the 2nd and 3rd Century sculptures of The Buddha) symbolizes spiritual insight. The practical “working out” is managed through the Noble Eightfold Path. As the name indicates, there are eight functions, and these are divided into three basic categories as follows:

Wisdom—The seed from which the next two categories grow. This seed is rooted in transcendent Buddha-Nature, not the self, symbolized by the lotus seat upon which Manjushri sits—the foundation; ground for his wisdom.

1. Right views

2. Right intentions

Ethical conduct—These are forms of wisdom expression, the structure for how wisdom takes shape.

3. Right speech

4. Right action

5. Right livelihood

Mental discipline—These are means for refining capacity and depth. As capacity advances, sight increases.

6. Right effort

7. Right mindfulness

8. Right concentration (Zen)

These eight are not necessarily sequential functions, although wisdom must infuse the other functions. In truth, prajna—wisdom is omnipresent, transcendent. The eight functions are not designed to acquire or create prajna. Our lack of awareness occurs not because prajna is absent but rather due to illusive mind. These eight functions are designed to reveal prajna by removing those dimensions of life that fuel the illusive mind. They are the “dust cloths” we use to remove obscurations. Rightly, they arise together, but this may mean that some aspects are lacking or weak.

Before concluding this introduction on seeing the unseen, a key point must be made: these eight steps along the Path are form expressions of emptiness. Some technical terms may help here. There are three aspects mentioned in Buddhist metaphysics to refer to the totality of Buddha-Nature. The three are the dharmakaya, the nirmanakaya, and the sambhogakaya. All three “kaya” aspects are already embodied within each sentient being, and fruition is a matter of coming to that realization.

The first—dharmakaya is the formless, indescribable unseen essence of which we have been speaking and the aspect we have referred to metaphorically as “The Wall.” This aspect of Buddha-Nature is called emptiness or the Void.

The second aspect— the nirmanakaya, is the enfleshed form of Buddha-Nature that we see when we look out upon life. This aspect is form. When we see as Sokai-An says, “man, woman, tree, animal, flower—extensions of the source.” When we see one another, we are seeing what the Buddha looks like in each of us.

And the third aspect—the sambhogakaya, concerns mental powers, with the ability of one’s mind to manifest with the five means of seeing. It is connected with communication, both on the verbal and nonverbal levels. It is also associated with the idea of relating, so that speech here means not just the capacity to use words but also the ability to communicate on all levels.

Wisdom transmitted and received through dreams, visions, and mystical experience comes via sambhogakaya. An awakening experience is modulated through sambhogakaya. This aspect contains elements of both The Wall and The Ladder—Emptiness, and Form. Actually, this is a misstatement since it seems to imply that the three aspects are somehow separate.

To see these as separate is only a matter of convenience. The problem with this view is that it carves Buddha-Nature up into separate pieces. Buddha-Nature is non-dual—a single unbroken reality. The “sambhogakaya” fuses these apparent pieces into a single aspect, thus removing the apparent duality. The Buddha calls the Void-Void—Not This; Not That yet also not-not This and not-not That. In other words, it is Not emptiness (alone) nor Form (alone), but instead, both emptiness and form fused into an inseparable bond. All three aspects are manifestations that are linked interdependently to transcendence/Buddha-Nature.

For lack of a better way of understanding these three, think “sambhogakaya” when the term “mind-essence” is encountered—the fusion of both emptiness and form but accessible to the mind. In other words, “mind-essence” is our doorway to transcendence using form. The dharmakaya is the Tathagatagarbha (Buddha-womb), the ultimate, non-differentiated source spoken of in the Heart Sutra where no eye, ear, or other form exists (yet all forms exist). You may want to re-read the posts on The Wall—Essence to get a firmer picture about the dharmakaya. This is the engine that provides motion to form, without which form could not move, and the bridge between form and emptiness is the sambhogakaya—“mind essence.”

What we do with wisdom transmitted from the source becomes a matter of transformation into form. When we pledge to emancipate all sentient beings, it is a matter of using the integrated power of the dharmakaya, conveyed and received through the sambhogakaya and actualized through the nirmanakaya. There is no power for emancipation without employing all three aspects. In the end, we must do something. If that “doing” is a matter of independence, cut off from our source, the “doing” will be ego-centric instead of Buddha-centric.

The Buddha is ever-present and is seen in every dimension. We see The Buddha when we use our fleshly eyes and look out upon ordinary life forms. We see The Buddha when we see through visions, dreams, mystical experiences using different eyes. And we see The Buddha in the Ultimate Realm of the dharmakaya, where prajnaparamita resides. The way of seeing reflects the degree to which we succeed in removing delusions that obstruct vision. All vision moves along the spectrum defined by the limits of the mundane and the supra-mundane. This is a continuum that floats on the surface of the mind. The more delusions, the more clouded our vision. The fewer delusions, the clearer our vision.

Prajnaparamita is ever-present—it doesn’t come and go. What does come and go are delusions which block and mask it. The Noble Eightfold Path is not a Buddhist version of a Jack LaLanne “spiritual self-improvement” program. Delusions which arise from the “self/nonSelf/ego” lay at the heart of the very clouds which obscure the truth, and to start down the Path with the presumption of building ego strength or using the “tools” of the Path for personal gain is a prescription for certain failure.

Functions—including the eight of the Noble Path— are “isness”—with definable properties, but they are connected to the “is” of “isness”—the divine spark that drives the engine of “isness.” This “is” of “isness” goes by many names, but as Lao Tzu said, “The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” Bodhidharma called this namelessness “The mind of Buddha and the Tao,” a nameless name that Lao Tzu first established. The Buddha himself referred to this namelessness as the Tathagatagarbha and the Dharmata. Dogen spoke of the indivisible, non-dual union of essence and appearance as “mind essence.” Huineng used the same expression. Sokai-An used the name “Great Nature” and “Great Self.” There are many names to point to the nameless mother of heaven and earth, but Sokei-An perhaps said it best. He said, “If you really experience ‘IT’ with your positive shining soul, you really find freedom. No one will control you with names or memory of words—Socrates, Christ, Buddha. Those teachers were talking about consciousness. Consciousness is common to everyone. When you find your true consciousness, you will not need the names or words of any teacher.” (The Zen Eye) In the days to come, I will share more about prajna, which will lay the groundwork for further discussion. Then in the eight days following, I’ll take these eight, one at a time.

Labels:

Bodhidharma,

Buddha Womb,

Buddhist scripture,

Dharma,

Dharmakaya,

Huineng,

Mind essence,

Nagarjuna,

nirmanakaya,

prajnaparamita,

sambhogakaya,

seeing,

Sokai-An,

The Wall,

wisdom

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)