Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Monday, April 2, 2018

The Four Horses of Zen

In the Samyutta Agama sutra, the Buddha told a parable of four horses. There is an excellent one, a couple of lesser horses and a bad one. He said the best horse runs before it sees the shadow of the whip. The second best will run just before the whip reaches his skin. The third one will run when it feels pain on his body, and the “bad” one will run after the pain penetrates into the marrow of his bones.

Already, not yet

The culmination of every spiritual journey is the realization of completion and unity. Many religions claim we are incomplete and must find the road to a far distant heavenly home.

Johnny Cash made famous the song In the by and by there’ll be pie in the sky, meaning there will be a reward waiting for us in heaven if we do God’s will here on earth. Because we imagine incompletion we seek completion. Because we misunderstand our source and ourselves, we desire fulfillment even though we are from beginning to the end already full. Our cup runs over with goodness and we remain thirsty for what is already ours.

Acceptance of the already and not yet is a seeming paradox. How can both be true at the same time? The answer as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin pointed out, is, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” Our true nature is spiritual, complete and there is nowhere to go. Our mortal nature is phenomenal, in a process, and we search for the already. We are like the man who looks through lenses, searching for the eyeglasses that sit upon his nose.

It was Zen Master Huang Po who expressed the doctrine of One Mind: “All the Buddhas and all sentient beings are nothing but the One Mind, beside which nothing exists. This Mind, which is without beginning: is unborn and indestructible. It is not green nor yellow and has neither form nor appearance. It does not belong to the categories of things which exist or do not exist, nor can it be thought of in terms of new or old. It is neither long nor short, big nor small, for it transcends all limits, measures, names, traces, and comparisons.”

Thus the idea of mind over matter is absurd. The mind is the matter in the exact same way that Emptiness is form (The Heart of Perfect Wisdom Sūtra). Every atom of our material body is nothing other than the perfect integration of the One Mind and looking elsewhere for what is already ours is a fools journey.

The parable of the Prodigal Son is a story that reveals this truth. The message of the Prodigal is the same as contained in the Song of Zazen written by one of the Zen giants (17th-century Hakuin Ekaku). Here are his words:

“How near the truth, yet how far we seek. Like one in water crying, ‘I thirst!’ Like the son of a rich man wandering poor on this earth we endlessly circle the six worlds. The cause of our sorrow is ego delusion.”

What can be seen blinds us and keeps us ignorant of what is unseen. So, on the one hand, we are deceived by the conditional, discriminate nature of what we can perceive and on the other hand, our true nature is unconditionally indiscriminate, ineffable but full. And out of our sense of incompletion, we are consumed by desire, not realizing that we already possess what we seek.

The noble winning poet Rabindranath Tagore captured the journey beautifully when he wrote, “The traveler has to knock at every alien door to come to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.”

So on this spring day, reflect on the labor of your life. Are you laboring for becoming complete? Or are you laboring to accept your never-ending completion? It makes a difference.

Labels:

abstractions,

abundance,

awaken,

Buddha nature,

delusions,

desire,

distortions,

duality,

ego-centric,

essential nature,

Hakuin,

Identity,

insecurity,

interdependent origination,

Mahayana,

Rinzai

Tuesday, March 27, 2018

Our overturned world.

| Artwork by Jim Sturgess |

Along the way of becoming educated about spiritual matters, I was graced with the writings of Patañjali who wrote sometime in India during the era spanning 500 BCE to 3rd century CE. He is credited with being the compiler of the Yoga Sūtras, an important collection of aphorisms on Yoga practice. Patañjali wrote about what he called kleshas (afflictions: causes of suffering) and maintained that there are only five of these. According to him, the five are:

Ignorance of the true nature of reality (avidya): The primal ignorance, which pervades all of creation. This ignorance is experiential, not conceptual, in nature. This is what Nagarjuna later referred to as the flip side of conventional truth (e.g., sublime truth) that could only be experienced, not rationally understood, but essential to awakening and being set free.

Misidentification (asmita): As individuals, we also have what is called an ahamkara or “I-maker” (ego). It is a single thought form, the delusional image of individualized existence.

Attachment (raga): Because the identification with the ego was false, to begin with, and because what is me is relatively small compared to the large surrounding universe (mostly composed of not me) a sort of existential terror and insecurity results.

Anger following loss (dvesha): In experiencing an object that gives us pleasure, we become attached and desire to continue the experience. When the experience becomes lost to us, we feel anguish and emotional distress. We blame the not-me for our predicament and lash out with a spirit of retribution.

Misunderstanding life and death (abhinivesha): Because of ego and attachment, a tremendous, continual, and habitual outflowing of our energy and attention occurs through our senses to the objects of the external world has been created. We imagine these objects as having a time existence governed by a beginning and an ending.

And then Patañjali said a remarkable thing—There is really only a single cause: the first klesha, ignorance of the true nature of reality and from this ignorance flows the other four. Thus by resolving this single klesha we see without spiritual blindness, realize that all before had been like a bad dream and awaken to an unbelievable realm of freedom.

I first began my spiritual journey many years ago when I reached a serious outgrowth of a lifetime of suffering. At first, I started with Hatha Yoga and later combined Hatha with Raja Yoga, also known as Aṣṭānga. Raja, or Aṣṭānga Yoga, is principally concerned with the cultivation of the practitioner’s mind using a succession of steps, such as meditation (dhyāna) and contemplation (samādhi). I was living in New York City at the time and began my practice at the Himalayan Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy, established by Śrī Swāmī Rāma, with headquarters in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, and a branch in New York.

For three years I continued at the Institute and eventually learned that dhyāna was the Sanskrit name for Zen. I was amazed that for that long I had been practicing Zen without knowing! I then switched over and joined a local Zen group. At that critical juncture, I was disgusted with my life and threw away what had taken 40 years to construct.

Later I left New York City to live at a Zen monastery located in the Catskill Mountains, upstate New York. Frankly, I was exceedingly naïve and spiritually uneducated, but I was in emotional trouble and consequently put myself in the hands of the abbot of the monastery. After nine months of near-continuous dhyāna, I experienced a radical transformation, which turned my world on its head.

What I had thought to be true of the world and myself was suddenly blown away and I was left in a state of mind completely unknown before. It was very much like becoming a child at the age of 40, which was both fantastic yet terrifying at the same time. What I knew well by then was how to live within what was essentially unreal (but I didn’t suspect that it was) and I had no idea how to live in this new world that suddenly came upon me.

It is very difficult to describe this new vision but perhaps the best way is to say that I was the entirety of the universe: there was no essential difference between me and everything else, including all people. Everything was unified!

The few years following that turned out to be magical as one (dare I say) miracle after another took over my life and ever so slowly I began to know how to live in this new world. It took me many years to adequately grasp what had happened but I became consumed with understanding, in order to pass on what had occurred. It was during this extended period that I read about Patañjali and started to know what had happened. I discovered that his vision was true for me.

Having experienced the turnover of my own primal ignorance, all four remaining kleshas fell into place and what had previously been so known, changed forever. Then I realized something most extraordinary: Had it not been for that lifetime of adversity there would have been nothing to motivate me to move to this better place. To make the choice of throwing away my previous life I had to know in my own bones how vacuous it was. And there was another thing: While in a state of ignorance, nobody has any idea they are ignorant or that there is an alternative. Instead, while in a state of ignorance, we all think it is just the way things are. We suffer but have no idea that we don’t need to. All of us are that way.

In his Two Truth Doctrine, Nagarjuna, said we live with two truths: the conventional and the ultimate, which we must be able to distinguish between, and unless we experience the ultimate we will never be free. What we all know as the conventional truth is our ordinary, conditional lives of right vs. wrong. That way leads through suffering to an awareness of the other truth. Until we know there is another way, it is impossible to experience it, unless we first completely give up the conventional. In that case, all we are left with is the ultimate.

In his commentary on the Sutra of Complete Enlightenment, Chan Master Sheng Yen said that nobody having good dreams wants to wake up. Only when we have nightmares are we eager to do so. None of us wants to suffer yet none of us can avoid it, and this desire to not suffer is what brings us all to the place where we say to ourselves, I’m not going to take this anymore.

The wisdom of this link between suffering and freedom is essential, yet counter-intuitive. The man credited with starting the current practice of Zen (Bodhidharma) pointed out the connection. He said: “Every suffering is a buddha-seed, because suffering impels mortals to seek wisdom. But you can only say that suffering gives rise to buddhahood. You can’t say that suffering is buddhahood. Your body and mind are the field. Suffering is the seed, wisdom the sprout, and buddhahood the grain.”

“People will only change when they have suffered enough.”—Winston Churchill

Monday, March 26, 2018

Where’s your mind?

|

| Where is it? |

A few days ago, I started this series of posts with a challenge: to find your mind, and since then, I have led you through a new way of seeing. Tomorrow I’ll conclude this series by sharing the Buddhist perspective of what the mind produces.

But today, we’ll consider a unique way of understanding your mind. But when this unique way is understood, it explains why we are so oriented toward hostility, violence, and alienation. The ordinary view is that the mind is a private and individual matter somehow associated with what resides between our ears.

My thoughts are unique to me, and your views are unique to you. From that perspective, difference is the norm. Consequently, opposition is typical, expected, and one ideology stands counter to another. One of us must be right, and that means the “other” must be wrong. But which one is correct? Both of us believe we are right, and neither of us thinks we are wrong, and this model of mind-in-the-head opposition is the commonly accepted view.

The Buddhist view is laid out in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra by the telling of a story, which concerns Ananda (first cousin of The Buddha). Ananda fell under a spell of a prostitute and subsequently is taught by his cousin, The Buddha, about why he fell. The teaching unfolds with The Buddha challenging Ananda to locate his mind. First, Ananda says, like the vast majority of the human race, that his mind is in his head. The Buddha shoots that notion down with an argument that can’t be overturned. Ananda then tries one answer after another, and each time, The Buddha shoots these down as well. In the end, Ananda never answers correctly, and the teaching of the Sutra is that the mind can neither be located nor found since everything perceptible is the not-to-be-found-or-divided mind.

In conjunction with the principle that no individual, uniquely special self exists, this view means that we all live within the commonly shared space of the real mind. This is no different from a quote I shared in a previous post (The road to an imaginary nowhere) spoken by Jesus. In the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas, Jesus is quoted as having said:

“If those who lead you say unto you: behold, the Kingdom is in heaven, then the birds of the heaven will be before you. If they say unto you: it is in the sea, then the fish will be before you. But the Kingdom is within you, and it is outside of you. When you know yourselves, then shall you be known, and you shall know that you are the sons of the living Father. But if you do not know yourselves, then you are in poverty, and you are poverty.”

It might be said that we are all virtual beings living in a virtual world, and consequently, it is not possible to indeed be in opposition to one another since we are all one. The opposition we to which cling as right is based on a false perception that we are separated and apart. What we see is a reflection of our mirror mind. It looks real, but we fail to realize that we are in the mirror—all reflections instead of reflected reality. We are like fish swimming through the sea of mind without knowing that there is such a thing as water. We are already in the kingdom. There is nowhere to go except for the sea.

Sunday, March 25, 2018

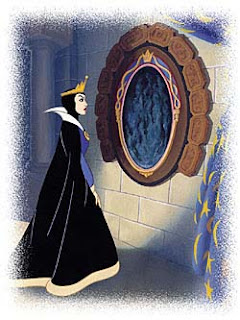

Mirror, mirror on the wall who’s the fairest one of all?

In a mirror, everything is reversed and all that can be seen is a reflection of something. What is right out here is left in there. Reality and an image are reversed and all that can be seen is a reflection of something. We can’t reach into a mirror and pull out anything real, but what we see looks very real.

What seems incomprehensible is that we have a mirror in us and like any other mirror, everything is a reflection of something real but only discernible as an image.

In our mind’s eye, we see an image of ourselves, and we call that image a “self-image.” It’s a product of our unseen mind. But since this image occurs in our mirror it is reversed and we take it to be real. Our ego is who we imagine our self to be and in our estimation, we are the fairest one of all. But in a mirror what we see as the fairest is reversed. In truth, our ego is our worst enemy.

Our ego is greedy, vain, vengeful, vindictive, vulnerable, defensive and willing to do anything, however awful to fend off perceived threats. And all the while the real us lies hidden beneath these illusions waiting to be unveiled.

Our mind is like an iceberg: The visible and tiny tip (ego mind) and what lies at the vast depths of us all is our true, and unseen mind without limits. The real us lies on the other side of that inner mirror and the qualities of the ego are reversed. Whereas our imaginary self is greedy, vain, ignorant, vengeful and possessive, the real us is complete, humble, kind, wise and compassionate, but the real us has no identifying characteristics.

Every means of perception functions internally. There is no such thing as external perception. Perception by every means occurs in our brain and is a reflection, but not the real thing being perceived. In truth, the entire universe exists only as images reflected in our brains. There is no perception of a self, no perception of a being, no perception of a soul and no perception of a person because a perception is only an image, a reflected projection that occurs in our brain.

We are real and not real at the same time. The images are unreal. Our reality is unseen. The images we see and take to be real are actually just perceptions. The reality upon which these images are based can never be directly accessed, yet we are here. Hermann Hesse, the author of Siddhartha, rightfully stated:

“There’s no reality except the one contained within us. That’s why so many people live an unreal life. They take images outside them for reality and never allow the world within them to assert itself.”

We live within the sea of unreality, which we understand as reality and never question this process.

Labels:

abstractions,

compassion,

delusions,

desire,

discrimination,

ego,

ego-centric,

false self,

Identity,

imaginary self,

mind,

Mind essence,

non-self,

One Mind,

perception,

reality,

self,

self-image

Saturday, March 24, 2018

Manifestations and mystery.

Do you drive a car? Wear clothing? Buy groceries at the store? These are everyday experiences that everyone knows well. We take such things for granted but no one is silly enough to think any of these just suddenly appeared out of nowhere.

Every objective thing—food, clothing, tools…every single thing comes from a source. Your car was manufactured in a plant somewhere. The parts to assemble it came from many different places, and the raw materials were dug from the earth. Where did the raw materials come from? We don’t know nor care so long as our car works we are satisfied.

How did anything become available? Because of desire. Somebody, at some earlier time, wanted things and they then began to think: How, they imagined, can such a thing be made? Who besides me might want it? How much will they pay? Can I make a profit?

Desire is the engine for production, thinking is the tool for bringing it into existence and your mind is the source of thinking, yet your mind can’t be found.

It’s a mystery! But the question must be asked: What is the taste of happiness? Do these ideas, these manifestations from our mind make us fulfilled? After a long time of indulging ideas and things, we develop an experience of being un-fulfilled. Then we are ready to let go of the engine of desire. Then we are ready to find the mystery that can’t be found.

Friday, March 23, 2018

An imagined you.

Do you have any idea who you are? Begin with this simple understanding: An idea is a mental image, otherwise known as a thought. When you imagine yourself you form an image. It may be a composite image constructed with many parts such as your standing vis-à-vis others, the values you hold dear, or just about any other contribution. But in the end, you have an idea about yourself, which you assume constitutes your being.

This process forces the matter of selfhood. Are you the result of this process—a composite image (a self-image)? Or are you the one who conjures up this image? If the former then you are in constant motion with continuously changing vagaries. In other words there is no permanent you, instead, you remain vulnerable and never at ease (e.g. dis-ease). On the other hand, consider the possibility that the real you is not, and has never been any sort of image but is rather the never-changing and constantly present, ineffable imaginer: The one doing the imaging that can never, ever be imagined.

In today’s world, we have a different name for a self-image. It goes by the name “ego” which if researched means “I” as when we say things like “I am a special being” (of some sort). And this ego understands itself as being uniquely different, special and in conflict with every other ego. It’s a world of me against you and if I am to win, you must lose.

Now this other entity, the imaginer, has no defining characteristics. If it did then it would be constrained to some characteristics but not others. One characteristic only has meaning when understood against some other characteristic such as up vs. non-up (otherwise known as down). Can anything be both at the same time? Our ordinary answer to that questions is no due to meaning and understanding, which is to say that everything can only be understood and have meaning when compared to something else: thus discrimination and discernment.

But how about this: My imagination is the same as your imagination and neither of these can be understood, just recognized as the wellspring of every thought and image. The imagination has one purpose only: to imagine. And the imagination has no limits or forms of difference. In truth, the imaginer is exactly the same from one person to another. We are all just a commonly shared mind without limit or constraining dimension.

Think about that! Better yet, don’t think about that. Just recognize this: You and I are the same non-thing, without limit.

Labels:

consciousness,

delusions,

discrimination,

ego,

emptiness,

enlightenment,

essential nature,

false self,

Form and emptiness,

Identity,

imaginary self,

insecurity,

Is-ness,

Mind essence,

selfless,

thoughts

Wednesday, March 21, 2018

Reflections of what's real

Study Zen for some time and you’ll begin to see the world in a very different way. You’ll discover there are two realms of life governed by opposite dimensions—mirror opposites—that are irrevocably riveted together. And these two are so conjoined they can never be taken apart. To remove one side removes the other, brings one into existence and the other side is there as well.

I’ve written about this principle many times but I can’t stop trying to refine and clarify that message because it is the essential crux of clear thinking. In truth, they are not two, just two sides of the same thing, thus One thing. The principle goes by the name “dependent origination,” which explains itself but seems most difficult to convey. It’s easy to fathom with simple examples, which cause us all to say, “Well, of course, that is true.” But the logical end of this principle entails the true nature of us all. We too have these two dimensions (which is One). One side of us is apparent and objective. The other side is invisible and ineffable; both of these dimensions are two different aspects of the mind, but not the mind as ordinarily thought of. This mind is “no mind.”

The father of Zen (Bodhidharma) said, “The mind is the root from which all things grow. If you can understand the mind, everything else is included.” And he said this to illustrate these two aspects. One of these is an endless illusion (that looks real) and the other is non-illusory and empty. The first is always moving like clouds moving across an immovable sky. What Zen teaches is that our only true mind is that sky that never moves. Instead, it functions like a mirror reflecting whatever comes before it.

Of course, the sky can’t see itself and our true mind can’t see itself. Instead, our true mind perceives what alone can be perceived: an infinite, perceptible realm of objects. The Buddha pointed out that, “We live in illusion and the appearance of things. There is a reality. We are that reality. When you understand this, you see that you are nothing, and being nothing, you are everything. That is all.”

The sky of mind is empty (otherwise known as void or Śūnyatā) and without this empty nature, nothing could ever exist due to this principle of dependent origination. For that reason, the Heart of Perfect Wisdom Sutra teaches that form (objective things—everything) is emptiness itself.

This is a most abstruse notion to put your head around. How, we reason, could perceptible and objective matter be the same thing as nothing? How can we be essentially empty when we feel full? That’s a different sort of full. Here we’re speaking about root essence and the opposite, or manifestations of root essence. And then we have to raise the question, what difference does it make—this seemingly esoteric nonsense?

And the answer to that question changes you and the world because the true us is that unseen, imperceptible reality: that true immovable and unconditional void, which is mind. And being such there is not an atom of difference between anyone. At that level of existence, discrimination ceases to exist and everyone is identical (and empty). Unfortunately, the perceptible anyone is discriminate and we enjoy discriminating against others, imagining ourselves as superior or inferior. Our ego loves comparison and it does that by placing one head higher (or lower) than another (our egotistical own).

When we remove this illusory ego we gut the power of evil and join the rest of the human race—all unconditionally the same. And that changes the entire game of life from despair to unified victory. This Zen stuff is critically practical and absolutely necessary for a world of equity and peace.

Labels:

awaken,

Bodhidharma,

Buddha nature,

Buddhist scripture,

conditional,

discrimination,

duality,

ego-centric,

essential nature,

false self,

Form and emptiness,

One Mind,

reality,

Zen

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

Who am I? Who are you?

Have you ever wondered what it must be like for a person living with Alzheimer’s? Such a person is lost in a never-ending dream with no idea who they are. They look in a mirror and see a stranger looking back at them. Apparently, some have the ability for momentary memory recall and then return to the enduring dream.

The Buddha said this is the way our life is. We are asleep, lost in an enduring dream and the challenge is to wake up and discover who we are truly. For most all of my life, going all the way back into my youth I was haunted by a question, which refused to go away: “Who am I?” I felt like I was trapped in a body and couldn’t touch the nature of my real self.

The question became a thorn of continuous pricking and wouldn’t leave me alone. Over and over it kept repeating until I thought I would go mad. And then one day it stopped all by itself and I knew the answer for myself, and in that instant, I knew the answer for everyone. We are buddhas. We’ve always been buddhas and will never stop being buddhas. And when I say that I don’t mean Gautama Buddha. I mean what the title “buddha” means: awake.

At that moment I woke up and remembered who I was. The fog went away and the question stopped haunting me. At that moment “I” disappeared and my real self (which was no self at all: just pure awareness appeared), but it was very confusing because the true me had no defining characteristics. At that moment I was nothing yet everything because a buddha is all there is. I am buddha. You are buddha. Every sentient being is buddha, and the buddha is mind.

In Zen literature, the question is constantly asked: “Why did Bodhidharma come to China?” And of course, the answer, which he gave, is to show the world the answer to this question that nagged me. We are buddha and the buddha is our awakened mind. There is no buddha except mind; no mind but buddha. We are all united as one indivisible reality, which is mind. When we sleep we are trapped in the dream of samsara. When we wake up we are free and find ourselves in Nirvana. We are different yet the same: sleeping and awake, always and forever.

Monday, March 19, 2018

First awaken your mind…

The famous Zen Master Bassui Tokushō (circa 1327–1387) was said to have told his students, “First awaken the mind that reads and then you’ll understand what you read.” We think we read with our left-brain because our language centers are located there. We thus imagine that reading is a rational and analytic process, but this is only half true. A parrot can be trained to speak but the bird has no idea what it is saying. We know people like that. The mouth moves but sheer nonsense comes out. More times than not we call such people politicians mouthing nonsense but saying nothing meaningful.

The mind that reads is not our rational mind. The mind that reads is a mind of insight, compassion, and wisdom. This is our true mind that can’t be found. The ego/rational mind can be found because it is full of images, and chatters like a Jaybird barking commands. The master of our rational mind orchestrates all of these commands. Our ego opposes anything and everyone who doesn’t kowtow. So we have both an unseen real self and mind, and an imaginary false self and mind. Only one is real, but can’t be found. The other is unreal but stands in clear view.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)