Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

Transformed Minds

Read it for yourself (Romans 12:2). For sure there may have been differences in how this prescription was offered from standard Buddhist teachings. However, Paul’s prescription is the same as what the Buddha taught—that unambiguous discernment is only possible through a renewal of mind: to purify and free the mind from self-centered discrimination.

Actually, these positions are harmonious—The Middle Way: Not this, Not that. Not not this, not not that. To explain: From the perspective of original mind there are transcendent truths and from the perspective of the phenomenal world, everything is relative. A “Dharma” means to comprehend or grasp transcendent truth—truth that lies beyond conditions of Christian, Buddhist or any other limitation. So on the one hand relativity is true and on the other hand, it is false—The Middle Way.

And what is the state of mind of little children? Well, we’d have to look at really little children since it doesn’t take very long before their egos begin to coalesce. Before that unfortunate emergence children still have their untainted original minds and they are like sponges soaking up, without judgment, whatever comes their way. It is a time of utter fascination where everything is new and wonderful! For little children seeing things as they are without bias is natural. They haven’t lived long enough to discriminate. Things just are what they are.

And in a similar fashion, Jesus taught “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.” Do you want to know what God looks like? To know, first get rid of what defiles your heart and mind. With nothing clouding your sight, then you’ll see clearly the kingdom of heaven. Recently the Pope said, “You cannot be a Christian without practicing the Beatitudes. You cannot be a Christian without doing what Jesus teaches us in Matthew 25.”

Saturday, May 20, 2017

A house of mirrors

|

| Our reflections. |

It’s dark, and you can’t see anything. Suddenly the lights are switched on. You’ve never seen the light before, so the glare hurts your eyes.

Days go by, but gradually your eyes adjust, and what do you see? Everywhere you look, you see people with smiling faces who seem to adore you, and these people are exuding love and tenderness all directed at you. They tickle you. They feed you. They comfort you when you’re sad and play with you, and little by little, you come to believe that you’re exceptional. These people are your parents and friends, and they are your mirrors.

That time is extraordinary, but it doesn’t last. Soon you move on and come in contact with other people. You and they relate to each other in the same way—like mirrors. You reflect them, and they reflect you, and little by little each, and everyone learns how to manipulate their environment to glean the best outcome, the ego dance begins, and our identities take shape.

So long as anyone stays in that house of mirrors, there is no alternative but to experience themselves as a reflection. But this manipulation game is complex and often frustrating, fraught with anxiety, fear, and tension. The players don’t cooperate. They want their way instead of your way. Why are these people not adoring you but instead demanding that you love them? Where are those adoring parents when we need them? Why can’t everyone just get along? Why can’t everyone see things as you do, think as you do, construct the world, as you want?

And the ego dance begins to come unglued, and you are lost, but what nobody realizes is at that moment of loss; that identity crisis is this is a blessing in disguise. Once that moment of disaster arrives, you are ready for the mirrors to fall away and find your true nature. And then, at last, you become the wholly complete person you’ve always been: The one looking into the mirrors; not the one reflected.

Friday, May 19, 2017

The Truth About Truth

In the early 1980’s speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill coined the phrase “The Third Rail of Politics” as a metaphor for addressing a topic too hot to openly discuss for fear of committing political suicide.

In that case, the topic was the looming bankruptcy of the Social Security System. Today that third rail is about many other systems ranging from our healthcare system, even the forbidden conversation of the political system governing our nation. Sometimes in order to solve a thorny problem, it is necessary to stick your neck out and risk getting it chopped off. Politicians, who depend upon the votes of the public for their survival, have more times than not chosen to say what they think the public wants to hear rather than what they need to hear. Every institution has its own “Third Rail” and Buddhism, as an institution, has one too: The Third Rail of Truth.

All of us think we know the truth (absence of falsity) and as a ordinary yardstick this works most of the time. So as a human society we have created norms and standards by which we measure the flow of life to determine whether or not something is true or false. It works loosely which means “most of the time”—but not all of the time. Sometimes what we thought was true turns about into “fake news.”

Ancient Indians believed they knew about truth and expressed their beliefs in the language of their time (Sanskrit). The Sanskrit word “Dharma” has a variety of definitions. One definition is “that which upholds and supports existence.” The root “Dhr” means to grasp (like in “understand”). An alternate definition is “Truth” as in Dharmakaya (Truth Body), which means the real/absolute, unseen body of The Buddha which all acknowledged Buddhist sutras say is The Buddha womb from which everything is made manifest: the pillar of The Buddha.

Many enlightened persons have used different names for this Truth Body. Huang Po called it “The One Mind,” without defining characteristics, Ch'an Master Linji Yixuan (Zen Master Rinzai) called it “True Man without rank,” and Master Bassui Tokushō would simply ask, “Who is it that hears?” I call it Mind Essence (Bodhidharma’s choice).

In an unexpected way these definitions of truth are not counter to the ordinary yardstick—the absence of falsity. But there are important subtleties to this understanding which open the “Dharma Gate” and allows the flow of wisdom, and one of the most critical subtleties pertains to attachment to truth itself. The question is both simple yet profound: Is truth absolute? Relative? Neither? Both? Transcendent to both absolute and relative? Easy to ask the question but not so easy to answer, at least in a way that doesn’t entail touching that third rail.

We pride ourselves as being moral people and as such we cling to ideas about what it means to be moral. This moral (sila) framework has been institutionalized with Buddhist precepts, one of which has to do with truth telling, so we use this as a guideline to govern our conduct. So how much of the truth do we tell? All of it? None of it? Some portion? Which portion?

Mark Twain, in his whimsical fashion said,“Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please.” Distortion seems to have now become the norm, even without getting the facts. Suppose we are talking about complete truth telling about ourselves. How exactly would that be done? Would we push the play-back button and share the second-by-second litany of every single moment of our present life? Do we share selected and edited versions? Edited according to what criteria? Who edits? Do you see the problem here? There is no solution to this dilemma when approached from the perspective of conditional reality. The matter is beyond comprehension.

In the sixth chapter of the Diamond Sutra The Buddha said an incredible thing regarding truth telling. He said,

“..if these fearless bodhisattvas created the perception of a dharma (truth), they would be attached to a self, a being, a life, and a soul. Likewise, if they created the perception of no dharma (no truth), they would be attached to a self, a being, a life, and a soul.” To this Kamalashila wrote, “According to the highest truth, dharmas do not actually appear. Thus, there can be no perception of a dharma. And because they do not appear, they do not disappear. Thus, there can be no perception of no dharma. This tells us to realize that dharmas have no self-nature.”

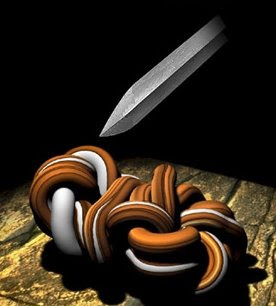

Let’s rephrase that: Truth does not have an independent status cut off from life. Truth is not a separate/abstract thing. Truth is a real thing which is reflected in the confused and unpredictable messiness which is life. Without wisdom this confusion becomes a Gordian knot so complex it is impossible to untie.

The ordinary way to fathom this complexity is to hold the feet of flow to the fire of inflexible standards and watch the sparks fly with the loud grating noise of friction, like a subway car screeching to a sudden stop. The infusion of wisdom turns this conflict upside down and allows the unfolding messiness to determine “expedient means” where the end (emancipation) dictates the appropriate (expedient) means.

Life is not a one size fits all situation. Chi-fo (aka Feng-seng) says, “Before we understand, we depend on instruction. After we understand, instruction is irrelevant. The dharmas taught by the Tathagata sometimes teach existence and sometimes teach non-existence. They are all medicines suited to the illness. There is no single teaching. But in understanding such flexible teachings, if we should become attached to existence or to non-existence, we will be stricken by the illness of dharma-attachment. Teachings are only teachings. None of them are real.”

To this Daoxin added, “Therefore the sutra (Nirvana sutra) says: ‘Since there are numberless (types of) capacities among sentient beings (the buddhas) preach the Dharma in numberless ways. Since the Dharma is preached in numberless ways, the meanings are also numberless. Numberless meanings are born from the One Reality. The One reality is formless, but there is no form that it does not give form to: it is called the true form. This is total purity.’”

This “One Reality” is of course the Body of Truth—the Dharmakaya: non-applied consciousness/Mind; the wellspring of all truth which is applied and conforms to the unfolding of life.

Our ordinary human nature desires certainty and predictability, but life is fluid and complex. Every sentient being has a unique track of causal linkages and karma, which defines unique forms of illness.

Daoxin said, “I expound this teaching (e.g., Essential expedient methods for entering the Path and pacifying mind) for those whose causal conditions and capacities are ripe for them...In the Prajna Sutra Spoken by Manjusri it says: ‘World Honored One, what is the one-practice samadhi?’ The Buddha said, ‘Being linked to the realm of reality (Dharmakaya) through its oneness is called one-practice samadhi. If men and women want to enter one-practice samadhi, first they must learn about prajnaparamita (e.g., perfect wisdom emanating from the unity of pure consciousness) and cultivate their learning accordingly. Later they will be capable of one-practice samadhi and, if they do not retreat from or spoil their link with the realm of reality, of inconceivable unobstructed formlessness.’”

To summarize this teaching. Truth is both absolute and relative. It is absolute within the realm of the Dharmakaya—the wellspring of all truth, where oneness reigns. And it is relative within the realm of our individual differences, where karma and causal conditions prevail. When our minds are pure (without retreat or spoilage; defiled with thought/non-thought) the Dharma Gate is opened and prajna flows freely. Prajna (e.g., wisdom) alone, the product of awakened awareness—the pipe-line from the Body of Truth—is capable of untying the Gordian knot of life’s complexity. Short of this we need guidelines, yardsticks, precepts and a tolerance for flying sparks and the loud grating noise of friction.

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

A Christian upgrade.

Unless you’ve recently been asleep at the switch you are without doubt aware of the “ransomware” computer attack that has disabled thousands of Microsoft users. Why did this have such a broad-spread impact? Because PC users never took the time to install the upgrade released by Microsoft.

The result has effectively rendered users of the Microsoft operating system null and void unless they pay a ransom.

This may seem like an odd lead-in to the topic of a “A Christian upgrade.” So allow me to clarify, and to begin let me ask a simple question. What is the relationship between the Old and New Testaments? Not a particularly difficult brain twister but an important question that has a parallel to the current ransomware crisis.

For those who don’t know, the word “testament” means covenant or contract: Two different religious operating systems; an old one and a new one. To be a genuine Christian means abiding by the standards set forth in the “new one,” but not both at the same time. The old was intended to be replaced by the new, but unfortunately too many never took the time to install the upgrade, and the result, just like with the ransomware attack, has rendered Christians null and void without paying a price.

And what is the price? Faux Christians who clearly do not comply with the standards of the New Testament and end up coming off as a hybrid, blending of “an eye for an eye”/tit-for-tat, vengeance seeking, hostile, and a quasi sometimes-professor of Christ: A really bizarre composite which is neither here nor there, which led Gandhi to say—I like your Christ, I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.”

Monday, April 17, 2017

The boredom.

|

| The endless waiting. |

It is said that war is 99% boredom and 1% sheer terror. It is. I know. I’ve been there and done that. The problem isn’t the terror. It’s the boredom: waiting for a moment you know will come with no idea of when.

It could come in the next moment or it could come in a thousand moments from now. Consequently, you live in a state of heightened expectation, and only a brief moment of release, that comes with the terror, accompanied by chaos. And then the cycle repeats and repeats endlessly. And it repeats endlessly because wars never end. It too keeps repeating endlessly.

We haven’t learned a damn thing since we walked out of the caves. One would think there is a difference between war and peace. There isn’t. The conditions might be different but the process is the same: 99% boredom and 1% sheer terror. And once again boredom is the issue, not the terror.

A thousand years ago in my high school algebra classroom, the teacher had placed a banner spanning above the blackboard. And the banner said, “He who perseveres shall attain the expansion.” At the time I thought she meant if we didn’t give up we would expand our minds with the knowledge of algebra.

It might have been her intention, but I have learned throughout life that perseverance is critical when a goal is in sight. In such a case the waiting, the not giving up; the boredom, ultimately wins the day. It is the price we pay to achieve the expansion, real or imagined, which might as well be the same thing since before something is in hand we never know if indeed there is a difference. So the reaching becomes a compelling force that keeps us all sane, believing that one day there will be a goal that is reached.

We seem to need the payoff. Without a sense that something of value will be attained, all the persevering, the waiting, the not giving up: the boredom, becomes meaningless, and we are like a leaf left floating along on a turbulent sea, toward nowhere.

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

The real deal.

Over the years that I’ve been poking here and there, examining a host of religious and spiritual paths, I’ve noticed that from the perspective of each and every discipline, the adherents nearly without exception claimed that their chosen discipline alone was the truth at the exclusion of others.

And another unavoidable observation

was (and is) that each adherent could quote chapter and verse from their holy texts

to support their claims but revealed their ignorance by claiming to likewise know

about other disciplines. Apparently, they differed with Mark Twain when he said,

These observations cast doubt over the entire lot and motivated me to dig deeper into various disciplines to avoid the same error. I may be a fool, but at least I try to keep it to myself. I agree with Mark Twain, who also said, “It is better to keep your mouth closed and let people think you are a fool than to open it and remove all doubt.”

I would be the first to admit that I don’t know in depth about all spiritual and/or religious paths, but I do know about mystical paths (particularly Zen and Gnostic Christianity) as well as the orthodox version of Christianity. I can make that statement, without apology, since I have a formal degree in Theology from one of the finest seminaries in the world and have been practicing, as well as studying, Zen for more than 40 years at this late stage in my life.

I must confess that I get a bit testy when someone, after spending at most a few minutes with Google, claims to know what has taken me many years to understand. And what annoys me even more is when a pastor, rabbi, guru, or other religious figures (who should know better) claims knowledge of matters they know nothing about yet makes unfounded claims and leads their “flock” into ignorance, either intentionally or not.

Now let me address what I said I would do some time ago: differentiate Zen from religions (particularly Buddhism) and I must start with an acceptable definition of religion. The broadly accepted definition is: “A communal structure for enabling coherent beliefs focusing on a system of thought which defines the supernatural, the sacred, the divine or of the highest truth.”

And the key part of that definition that is pertinent to my discussion here is, …a system of thought… While it may seem peculiar to the average person, Zen is the antithesis of …a system of thought… because Zen, by design, is transcendent to thinking, and plunges to the foundation of all thought: the human mind.

And in that sense it is pointless to have an argument with anyone about this, rooted in thinking. That’s point # 1. Point # 2 is that Zen, as a spiritual discipline, predates The Buddha (responsible for establishing Buddhism's religion ) by many thousands of years. The best estimate, based on solid academic study, is that the earliest record of dhyāna (the Sanskrit name for Zen) is found around 7,000 years ago, whereas the Buddha lived approximately 2,500 years ago. The Buddha employed dhyāna to realize his own enlightenment, and dhyāna remains one of the steps in his Eight Fold Path designed to attain awakening. Thus, pin Zen to Buddhism's tree is very much akin to saying that prayer is exclusive to Christianity and is a branch of that religion's tree.

While it is stimulating and somewhat educational to engage in discussions regarding various spiritual and/or religious paths, the fact is we have no choice except to tell each other lies or partial truths. Words alone are just that: lies or partial truths concerning ineffable matters. That point has been a tenant of Zen virtually since the beginning. Not only is this true of Zen, but it is also true of all religious and spiritual paths.

Lao Tzu was quite right: “The Way cannot be told. The Name cannot be named. The nameless is the Way of Heaven and Earth. The named is Matrix of the Myriad Creatures. Eliminate desire to find the Way. Embrace desire to know the Creature. The two are identical, but differ in name as they arise. Identical they are called mysterious, mystery on mystery: the gate of many secrets.”

In the end, none of us has any other choice except to employ illusion to point us to a place beyond illusion. I leave this post with two quotes, one from Mark Twain and the other from Plato. First Twain: “Never argue with stupid people, they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.” And then Plato: “Those who are able to see beyond the shadows of their culture will never be understood, let alone believed, by the masses.”

When I make statements, I know that I am telling partial truths, and I am stupid to argue. It makes both of us more stupid. That’s the real deal and should make us all a bit more humble and less sure that our truth alone is the only one.

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

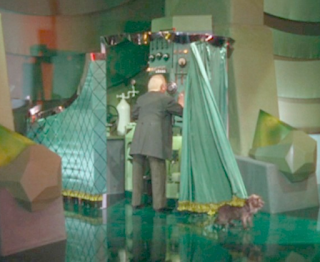

The wizard beneath our Oz.

To those familiar with the story of The Wizard of Oz—a wizard nobody had ever seen, controlled the Land of Oz. In a way, this wizard inhabited the entirety of Oz with his unseen presence.

The Sutra of Complete Enlightenment says,“...the intrinsic nature of Complete Enlightenment is devoid of distinct natures, yet all different natures are endowed with this nature, which can accord and give rise to various natures.”

On the surface, this statement sounds arcane. Trying to imagine something which has no nature but is the basis for all nature is puzzling. Whatever that is, so says the sutra, is “intrinsic,” which means belonging to the essential nature of whatever is being contemplated, in this case, “all different natures.”

The only way this can be understood is that Complete Enlightenment is ubiquitous. It doesn’t come and it doesn’t go since it is ever-present and thus does not depend upon the conditions of space/time. The word “transcendent” comes to mind.

But, so we think, if Complete Enlightenment is devoid of nature, how is it possible to be aware of it? It almost sounds as if we’re talking about something which is both empty and full at the same time—transparent yet concrete; the ground out of which everything grows but is itself invisible. By reading further in this sutra we find this: “Complete Enlightenment is neither exclusively movement nor non-movement. Enlightenment is in the midst of both.”

In other parts of Zen literature, we learn that it is the movement of ideas wafting across our screen of consciousness that constitutes what we call “mind.” And it is thus the goal of zazen to stop this elusive movement and thereby reveal our true nature. It is the nature of our Mind to create images to represent concepts and ideas. But the mind of concepts is an abstraction and the result of rational thought. The true Mind is accessible through intuition (e.g., inner insight), not thoughts. And when challenged to imagine something which is not an idea, we come up short. We can’t imagine enlightenment because in itself it is imageless. Consequently, when we try, we fail. And it is in the midst of that failure that enlightenment is understood.

As convoluted as this sounds, this insight is Complete. If there is nothing to see, then Enlightenment is seen everywhere we look. There is thus nowhere that Enlightenment can’t be found. When we see a tree, we’re seeing the manifestation of Enlightenment. When we see the sunrise, we’re seeing Enlightenment; A dog—Enlightenment; Another person—Enlightenment; Anything/Everything—Enlightenment. All perceptible forms, we find are the eternal manifestation of Complete Enlightenment. And why would that be? Because pure consciousness has no form, yet everything is perceived out of that.

Because we have never seen Complete Enlightenment, as an exclusive and separate entity, we think it must be a mystical matter, perceptible to only a select few and we imagine that this mystical state will be the result of adopting a state of mind which, for most people, is unavailable. This is exceptionally unfortunate!

Hakuin Zenji (circa1689-1796) is famous for his “Song of Zazen” in which he says, “How sad that people ignore the near and search for truth afar: Like someone in the midst of water crying out in thirst; Like a child of a wealthy home, wandering among the poor.”

The clear insight of these teachings is that enlightenment is the fundamental ground of our existence. It is everywhere we look (yet never found). It is our intrinsic true nature, without which we could not exist. You might say, consciousness is the wizard beneath our Oz.

Monday, March 20, 2017

Is there a “Self?”

|

| Fabrication? Or real? |

We humans have a big problem: language. We have invented words for everything regardless of whether the thing is ineffable or not. The opposite of a “thing” is “no-thing/nothing.” A thing is perceptible and nothing is not. When the words we employ relate to perceptible matters there is less of a problem, but even then words mean different things to different people. I’ve written previously concerning this dilemma in a post: Does suffering have a positive side?

All humans imagine they have a unique identity or personality which is, in part, the constituents of a “self.” When we imagine ourselves we draw together composite components, such as how we think others see us, and what we think of ourselves. We dress this ego-self up with variegated clothing of profession, education, relationships, and many other factors we consider important, and end up with an internally perceptible “self-image” (ego). What should be apparent (but remains obscure) is that all images (self-included) are neither real nor the nexus of perception. The logic of this is peerless and we have been educated to know the difference between a perceptible object and an imperceptible subject (the ineffable person we imagine ourselves to be).

In a recent post (Our overturned world) I spoke about the writings of Patañjali who lived in India during the 2nd century BCE. He is credited with being the compiler of the Yoga Sūtras, an important collection of aphorisms on Yoga practice. Patañjali wrote about what he called kleshas (afflictions: causes of suffering) and maintained that there are only five of these. According to him, we have what is called ahamkara or “I-maker” (ego). It is a single thought form, the delusional image of an individualized existence. This premise is fully embraced within Zen and is the foundation upon which the conviction of “no-self” is based.

It is our nature to label everything and in the case of our true, subjective selves, we apply the name of another self (now we have two, both fabricated). There is the perceptible, objective ego/self and an ineffable subjective Self. But we only apply the label of Self due to our inability to articulate or define pure consciousness, otherwise called “The Mind.” In other words, we know the mind is present by virtue of actions.

This matter is conflated due to seemingly conflicting Buddhist teachings. On the one hand, it is standard Buddhist teachings that we have no self (anattā). And on the other hand, there are Buddhist Sūtras that teach a higher Self, such as the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtras, (one of which The Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra—contrasting these two selves). In Chapter 3 (On Grief) of this Sūtra, the Buddha taught, what he called “four perversions.” He said that the true Self signified the Buddha, the eternal signified the Dharmakāya (the Mind—literally “truth body”), Bliss signified the lack of dukkhā and Nirvana/the Pure, signified the Dharma. He went on to say that to cultivate impermanence, suffering, and non-self has no real meaning and said,

“Whoever has these four kinds of perversion, that person does not know the correct cultivation of dharmas. Having these perverse ideas, their (the lost) minds, and vision are distorted.” He continued, “If impermanence is killed, what there is, is eternal Nirvana. If suffering is killed, one must gain bliss; if the void is killed, one must gain the real. If the non-self is killed, one must gain the True Self, O great King! If impermanence, suffering, the Void, and the non-self are killed, you must be equal to me.” In this same Sūtra, the Buddha said, “Seeing the actions of body and mouth, we say that we see the mind. The mind is not seen, but this is not false. This is seeing by outer signs.”

This is confusing, but after much study, you come to realize that the labels of “Mind” and “Self” are used interchangeably. In any case, (depending on your preferences) neither the Mind nor the Self can be seen, simply because these are arbitrary words for consciousness: the nexus of all perception. In fact, the Self is just another name for Buddha-dhatu/the true immaculate Self—the only substantial, yet unseen reality.

After all else, we must recognize the limitation of words and, as Lao Tzu said, “The Tao that can be spoken is not the enduring and unchanging Tao. The name that can be named is not the enduring and unchanging name.” The word “Tao” was the same word the Buddha used for “the Mind/Self.” The clue should be, that a name is not the same as what the name represents. Names are expressions of substance but they are nevertheless mental images intended to point to substance, and in the case of a self, the substance in question if ineffably indefinable. A rose by any other name smells as sweet.

Monday, March 13, 2017

The sea of bliss.

|

| The heart of darkness and light. |

Until we have seen someone’s darkness, we don’t really know who they are. Until we have forgiven someone’s darkness, we don’t really know what love is.

To one trapped in a bondage of the mind, there is a darkness to move beyond that can cloud our sense of being and our capacity to love. The idea of moving beyond seems to imply movement toward a goal: something not present. There is, however, another way to understand this obstruction: The darkness that impedes our capacity to love. A drop of water, dark or not, taken out of the great sea, is certainly divided from the indiscriminate source but when it returns to the source, it becomes absorbed and can’t be found. It is then lost in the sea of love.

This is an easy example that displays the difference between duality and unification. Bodhidharma illustrated this by speaking of the body of all truth, where everything is One. His commentary on the Lankavatara Sutra teaches there are two aspects of life: The discriminated/perceptible, and the unified/ineffable—bound together in a manner too marvelous to understand. He said: “By tranquility is meant Oneness, and Oneness gives birth to the highest Samadhi which is gained by entering into the realm of Noble Wisdom that is realizable only within one’s inmost consciousness…The beginning chapter of this sutra concludes in this way... “In this world whose nature is like a dream, there is place for praise and blame, but in the ultimate Reality of Dharmakaya (our true mind) which is far beyond the senses and the discriminating mind, what is there to praise?”

So where is the source of hope and tranquility? Our hope lies imperceptibly beneath impermanence at the heart of decay. And what is that heart? Huang Po (Obaku in Japanese; 9th century China) was particularly lucid in his teaching about this. In the Chün Chou Record, he said:

“To say that the real Dharmakāya of the Buddha resembles the Void is another way of saying that the Dharmakāya is the Void and that the Void is the Dharmakāya ... they are one and the same thing...When all forms are abandoned, there is the Buddha ... the void is not really void, but the realm of the real Dharma. This spiritually enlightening nature is without beginning ... this great nirvanic nature is Mind; Mind is the Buddha, and the Buddha is the Dharma.”

This perspective, however, is a bit like looking in a rearview mirror that reflects darkness once you’ve found light. While in the darkness, no light is seen. To go looking for the void beyond darkness takes us into the sea of nondiscrimination where compassion and wisdom define all. And once there, in this eternal void—the source of all, we fuse together with all things and realize that dark and light are just handles defining the seeming division between one thing and another. We are then absorbed by the vast and endless sea of bliss and tranquility. We are in a home we never left.

Thursday, March 9, 2017

Getting to the other side

If I were wishing to cross a river to the other side I would need some means to get there. Maybe I would choose a boat and oars and propel myself across. But before I went to the trouble of obtaining the boat and oars, and expending the effort to cross, perhaps I might consider why I want to cross in the first place. Maybe someone has told me that on the other side it’s a better place than where I stand and I decided that they might be right.

The point is that we do things like moving from point “A” to point “B” for what we consider to be good reasons. We can’t know for sure whether or not our reasons are valid until we make the trip. Then only can we know, because we then have an actual experience of the other side to compare with the opposite shore. We refer to this as “The grass is greener on the other side of the fence.”

But as we all know, oftentimes the grass is not greener and then we have an embarrassing conundrum to deal with. Do we acknowledge this error in judgment, and attempt to come to terms with how we made the error? Or maybe we take another tack and pretend that the other side really is greener (when it is actually not) to justify our actions. Many people are remiss to acknowledge an error, feeling the pain of a diminished ego and humiliation. Rather than take the hit they choose to deny reality and continue to make the same mistake over and over again. Does this sound familiar? It should since we are living in a time when error upon error is being made, with no admission of wrongdoing.

This line of thought is leading to a discussion on crossing the river from “carnage” to a better place and the presumptions we use to support the making. In standard Buddhist practice, the presumption is that we move toward enlightenment by embracing a given set of precepts that we believe will purify our being and thus facilitate an experience we think of as enlightenment. If we have never crossed over we can only guess about the turf on the opposite shore. Maybe it will be greener and maybe not. But how would we know until we actually cross over? Perhaps the presumption is correct—that precepts produce the desired effect. But of equal value is to question the trip and the means to get across.

The Buddha probably wrestled with this predicament and learned through experience that his presumptions were flawed. His own prescription didn’t work. The more important question is a matter of order. Did The Buddha’s enlightenment come following the formula, or did the formula follow his enlightenment? This question is rarely considered but it is “the” question. Is it possible, for anyone—The Buddha included—to manifest ultimate goodness while enslaved within the grip of an ego? Which is the chicken and which is the egg? Or does genuine goodness and the evidence arise together?

The presumption of cause and effect (e.g., karma) leads us to examine in this way—Goodness (cause) and enlightenment (effect) or, enlightenment (cause) and goodness (effect)? One side of the river is a corrupted nature (an ego) which may desire to do good but is lacking the capacity, and on the other side of the river is the well-spring of goodness, but is lacking the arms and legs needed to propel us across. So long as anyone thinks in this divided manner they will never be able to move, much less across the river. Why? Because motion—any motion, and particularly the motion of enlightenment—is not a function of division but of unity.

The Buddha’s enlightenment occurred once he had surrendered from the Gordian Knot—the insolvable quandary which demanded this choice between cause and effect. Should he choose the side of ultimate goodness? Or ultimate depravity? That dilemma still stands as the ultimate challenge and there are no options to solve it today that didn’t exist in the time of The Buddha. The answer today, as then, is let go. It is not now, and will never be, possible to untie this knot by traveling a path other than The Middle Way.

Goodness and the well-spring of Goodness arise together and disappear together. We are both at the same time, or we are neither. Not cause and effect, but rather cause-effect. We can’t earn goodness from the center of self because self serves self alone. When we exhaust this center, goodness bubbles to the surface naturally. It can’t be forced upward through the filter of ego. That plug is too strong to allow passage. When it is removed the flow begins, and until that happens the only movement which can happen originates from the ego.

And then we discover that enlightenment is not one shore against the other shore. Enlightenment is both shores and the river and all of life. It is not a destination but rather an experience of goodness which flows naturally, but only when the obstacle is removed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)