Birds and thoughts fly through the sky of mind. When they are gone we’re left with the sky of wisdom and compassion.

Showing posts with label abstractions. Show all posts

Showing posts with label abstractions. Show all posts

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Making the Trade

But over time, these forms no longer nurtured you, and you wanted a deeper level of meaning in your life. And then you learned that it might be possible to get what you desired but to do that, you’d be required to give up everything you had acquired and throw away all of the money you possessed. At that point, you’d be faced with the mother of all choices—relinquish everything you possessed (which was real and tangible but no longer valued) and leap into the void of uncertainty on the bet that there would actually be a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Reifying Illusion

“Reifying”—An uncommon but important word. It means being confused about the nature of something fundamentally not real, but we believe it is. For example, we firmly believe our identity is substantially real, yet it changes as life ebbs and flows.

Imagine that you go to a movie. When you enter the theater, you have no doubts about the film’s nature. You know that what appears on the screen is pure illusion. The movie might be quite involving to the point that you actually get swept up and affected, but never do you think you are actually in the movie. If you cannot distinguish the unreal nature of the movie from your normal reality, you would be called delusional and would be guilty of reification.

Our normal understanding of reality is that we are not “in the movies,” and we can thus compare this “normal” condition against other states of consciousness to establish whether or not they are real. It never occurs to us that the conditions we perceive are no better than what we see on the theater screen, yet there is very little difference between the two.

The only difference is where the movie screen is located. The real movie screen is actually in our brains. Even the movie screen in the theater can only be perceived in our brain—we see two movies: One which we assume is in the theater and the other, which is actually a projection in our brain.

We have learned through modern neurology the same as what the Buddha said 2,500 years ago—That what we take for granted as real is actually an illusion. It is impossible to perceive anything without a brain, and our sense of objectivity is the result of projected images. Not knowing this, we then reify these images: Believing that the abstractions are real. If that is not bad enough, we assume that our real self (e.g., true Self) is nothing more than a perceptible object and label it a self-image (ego).

Our entire sense of reality is upside down. It turns out that what we have understood as real is actually nothing more than illusions and what we have thought was unreal (our true nature) is actually the only reality that exists. Our perceptions have fooled us and left us with a genuine mess. The result of this glitch is that we end up clinging to vapor and then suffering as it slides through our fingers. Little did we know that The Buddha has been right all along.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Pie in the Mouth

In probing the layers of human physiology and psychology, Paul Broks, neuropsychologist/philosopher, leads us through a haunting journey in his book Into the Silent Land.

It is hard not to be stunned by reading his dissecting view of what it means to be human. We take so many things for granted. That, which is basically inanimate “meat,” can and routinely does animate with consciousness, cognition, imagination, feelings and every other aspect of our condition seems to float by as a given. This fundamental mystery is so ingrained into our being that it goes unnoticed, but not by Broks.

He asks alarming and provocative questions such as “Am I out there or in here?” when he portrays an imaginary man with a transparent skull, watching in a mirror his own brain functions. He notices, for us all, that the world exists inside the tissue residing between our ears. And when the tissue is carefully examined, no world, no mind, no ego/self, no soul, no perceptual capacities, nor consciousness—nothing but inanimate meat is found. Unable to locate, what we all take for granted, he suggests that we are neither “in here” nor “out there,” maybe somewhere between the space between the in and the out, and maybe nowhere at all.

Yet here I am writing these words, and there you are reading them, and so it has always been. We are nowhere and we are everywhere. Not to be found yet fully here. We are like holograms; mind manifestations, which appear or vanish when we are plugged in or out. The inescapable conclusion that arises from such a probe is that we are spirit. No other sensible conclusion is possible. This great mystery has puzzled and confounded humans since the dawn of time, thousands of years before there was the science of neurophysiology or neuropsycholgy. How is it possible that we function as we do, out of what is basically meat? The answer remains hidden beneath veils of mystery.

Anyone familiar with the Heart Sutra can’t help but observe the coincidence between Broks probe and the message contained in the sutra—that there is both delusion and non-delusion. There are human aspects rooted in illusion (which have no substantial reality) and there is the realm of all-pervasive, ever-present perfect peace which is, itself formless and void but nevertheless the well-spring of our existence. There is nothing to be found nor attained in the meat. And because of this “...The Bodhisattva relying on Prajnaparamita has no obstruction in his mind.” Prajna (wisdom)+ Paramita (perfection) means perfect wisdom. Such enlightenment comes with the acceptance of this great mystery, that there is nothing to be found yet we exist as manifestations of what we call God. That is the great mystery, not the animated meat!

And what is of equal fascination is how the Western mind grapples with this mystery versus how the Eastern mind does. Whereas the Eastern mind accepts the mystery as a given, the Western mind wants to probe beyond and explain the mystery—to understand it. To western thinking it is extraordinarily difficult to set the matter to rest, to drop it and just let it be. To Zen, a “nose” is not a nose (the convention of N_O_S_E) but rather the tweak of the object that lies between the eyes. Zen wishes us to wake up and feel the tweak—to move beyond all conventions, abstractions and models—and savor life as it is rather than to describe or understand it.

“If one reaches the point where understanding fails, this is not such a tragedy: it is simply a reminder to stop thinking and start looking. Perhaps there is nothing to figure out after all: perhaps we only need to wake up.” (Zen and the Birds of Appetite)

To Zen, even conventions such as “The Void,” “God” and “Self” are not to be understood but are rather to be experienced. Such a thrust moves us beyond holographic understandings, beyond ideas and beliefs systems—conventions about life—into the realm of life itself. Zen is about pie in the mouth, savored on the tongue instead of a perfect description of the pie that exists only in the holograms of our mind.

Labels:

abstractions,

bodhisattva,

Buddhism,

delusions,

ego,

emptiness,

enlightenment,

God,

Heart Sutra,

Lineages,

mind,

Paul Broks,

prajnaparamita,

Religion and Spirituality,

self,

void,

wisdom,

Zen

Sunday, January 13, 2008

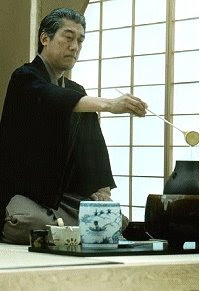

Drinking Tea

In my last posting, I ended with a confusing idea. This “...just go on suffering anyway” idea sounds wrong-headed, so I must explain. Suffering is what is caused by attachment and attachment can’t be avoided so long as we are subject to dependent origination and causal linkage. In my example of a driver and what is driven, combined with a linkage between cars and accidents, the conjunction results in suffering.

The only way to have a different, non-suffering outcome is to detach drivers from cars and create a different causal linkage that doesn’t entail accidents. But this is a purely fictitious/after-the-fact fantasy. In the first place, it is impossible to detach drivers from cars since drivers arise with what they drive (cars) and no one can wind time backyards and change circumstances in a way that may seem more desirable.

The opposite of suffering (bliss) is not something that entails circumstances nor subject/object separation. Suffering and bliss occur in the same realm. Bliss has nothing to do with circumstances. Bliss is unconditioned—transcendent to all circumstances and results from accepting life just the way it is and not being disturbed. And why would it not be disturbing? It would be disturbing—always—at the conditioned level because of dependent origination and causal linkages and never disturbed at the unconditional level. We are not one kind of condition vs. another kind of condition. We are both conditions and unconditions at once.

The truth is that we are not carved up into mutually discrete sections like some butcher shop chart of a cow. We are an integrated whole. We speak as though we are parceled up but that manner of speaking is purely for convenience purposes. The relevant issue is who we are and how we respond to life, not what happens beyond our control (which is most everything). When we identify ourselves with the roles we play or the infinite abstractions of self, we will always suffer because these ways of identifying are not who we are. Who we are is unconditional and always secure. So when the tides of life flood us we will suffer yet we won’t.

We all have relationships. I am both a husband and a father. A husband is a husband because there is a wife. A father is a father because there is a child. When my sense of identity is attached to those roles I am vulnerable and subject to suffering. Why? Because when we have relationships we form conditioned expectations of performance. So long as our relationship partner performs up to expectations everything seems satisfactory. But let circumstances go against our expectations, then there are problems.

We will never find peace when we place our hopes for fulfillment in another person. So long as we do that we’ll be disturbed. The correct way is to get clear about who we really are (selfless and without conditions). Then we can have fulfilling relationships which are filled-full to begin with, not as a result of what our partner does or doesn’t do. It is ludicrous to speak of relationships which are detached. Such a thing can’t exist. Husbands are attached to wives in the same way that drivers are attached to cars. There is no such thing as a husband without a wife. That would be an ex-husband or a widower, neither of which would be a husband. This is what I meant when I said—“When we drink tea, we just drink tea, with nothing added. No honey (thoughts)—just pure tea.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)